Wilderness and Forest Cover in the Tropics:

How Much Wild Land Remains?

The Extent and Health of the World's Tropical Forests and Wild Land Today | October 13, 2025

Last updated: October 13, 2025

This article is entirely independent and contains no sponsored content or affiliate links — it’s written to provide unbiased information for travelers. Title photo by Lingchor on unsplash.com.

Introduction

Tropical forests are Earth’s most biologically rich and ecologically vital ecosystems—home to the majority of all known species and essential regulators of the planet’s climate. Yet these forests are shrinking and fragmenting at an alarming pace. Across South America, Africa, and Asia, once-continuous wildernesses have been carved into isolated remnants by roads, farms, and settlements. Only a fraction of the world’s original tropical forests remain intact, and their condition varies dramatically between regions. Understanding what portion of these forests still qualifies as true wilderness—and where those remaining strongholds lie—is essential for gauging the planet’s ecological health and the future of biodiversity.

This article provides a region-by-region analysis of the world’s remaining tropical forests, drawing on recent studies and satellite data to assess both the extent and quality of surviving forest cover. It begins by defining what constitutes a “healthy” or “intact” forest, then examines global statistics before delving into detailed sections on South America, Central America, Africa, Asia, and Australasia. Each section highlights key wilderness areas, rates of loss, and contrasts between lowland, mountain, and swamp forests. The discussion concludes with an integrated perspective on the global patterns of deforestation and fragmentation, emphasizing how geography, accessibility, and land use have shaped the fate of the tropics—and what these trends imply for conservation in the decades ahead.

Tropical Forests Overview

- Intact Forests (36%)

- Degraded (30%)

- Deforested (34%)

- Amazon — 72% of Intact

- Africa — 20% of Intact

- Asia — 7% of Intact

Remaining Intact Forest by Region

Key Notes

- Amazon remains mostly intact (70–85% original extent).

- Central America: Extremely fragmented.

- Africa: Congo Basin strong; West Africa only 10–20% of original extent remains.

- Asia: Lowland forests nearly gone; some upland refuges persist.

- Australasia: New Guinea remains ~70% forested, highly intact.

Defining “Healthy” Tropical Forests

“Healthy” tropical forests can be thought of as large, contiguous areas of natural forest (primary or mature secondary) with minimal human disturbance. These forests have few internal clearings and are not bisected by major highways or roads. By this definition, an intact block of rainforest remains “healthy” even if it includes some secondary regrowth, so long as the canopy is largely continuous and human impact is low. Truly “very healthy” forests would be those that are fully intact primary forests – essentially wilderness areas – with no major fragmentation (no highways, towns, or plantations inside)[1]. Once a wide road or other barrier cuts through a forest, it effectively splits one habitat into two smaller ones, disrupting wildlife movement and gene flow for many species. For example, in the Amazon, it’s estimated that 41% of the rainforest lies within 10 km of a road, reflecting how roads have carved up previously continuous forest. This fragmentation is critical: about 95% of deforestation in the Amazon happens within 5.5 km of a road, showing how road networks act as “arteries of destruction” that open forests to logging and land clearing[2]. In assessing tropical forest health worldwide, therefore, both the quantity of remaining forest and its quality (contiguity and intactness) must be considered.

It’s also important to distinguish true forests from mere tree cover. Plantation monocultures (such as oil palm or rubber), urban trees, or narrow strips of riverside vegetation might count as “tree cover” in satellite images, but they do not function as intact forest ecosystems. Statistics based purely on tree cover can be misleading – for instance, a country might report high tree cover that includes plantations or young regrowth, even while its primary forests have been largely destroyed. In this report, “forest” refers to natural tropical forest (primary or long-established secondary), excluding plantations and highly fragmented patches. We focus on how much of the original forest extent remains and how much of that is still in a healthy, contiguous state, as opposed to degraded or isolated fragments.

Global Status of Tropical Forests

Tropical forests once blanketed vast regions of the planet, but human deforestation has dramatically reduced and fragmented them. According to a comprehensive 2021 analysis by Rainforest Foundation Norway, only about one-third of the tropical rainforest that once existed remains intact today. Of the roughly 14.5 million km² of tropical rainforest that existed before significant human interference, 34% has been cleared completely, and 30% has been degraded (partially logged or thinned), leaving 36% still intact as of 2019. In other words, roughly two-thirds of the original tropical forest area has experienced some level of loss or degradation. Even among the remaining tropical forests, almost half are classified as degraded rather than pristine[1]. These degraded forests still have tree cover but suffer from reduced biodiversity and ecological function due to logging, fires, and fragmentation.

Crucially, the intact third of tropical forests is not evenly distributed around the world. The vast Amazon Basin in South America contains the lion’s share of what remains: about 72% of the world’s remaining intact tropical rainforest is in the Amazon alone. In contrast, tropical Asia has been hit hardest by deforestation – Asia holds only ~7% of the world’s intact tropical rainforest today[1]. Africa’s rainforests (mostly in the Congo Basin) make up the rest (roughly 20% of global intact rainforest). This means that tropical America (Amazon and other Latin American forests) still retains a large expanse of unbroken forest, while Asia’s forests are mostly fragmented or gone, with Africa falling in between.

It’s worth noting that intact primary forests are irreplaceable in terms of biodiversity and climate regulation. They store more carbon and house more species than degraded forests or plantations. Unfortunately, the current trends are negative: between 2002 and 2019 the tropics lost about 571,000 km² of rainforest (an area larger than France) to outright deforestation. When degraded areas are included, the concern is that we are pushing tropical forests toward an ecological “tipping point” of collapse. Scientists warn that as fragmentation and degradation increase, tropical forests could lose their ability to sustain rainfall and biodiversity, potentially converting to drier ecosystems. Signs of such stress are already visible in parts of the Amazon[1].

Despite these challenges, the remaining intact forests still represent a huge area – “half the size of Europe” in total area – and thus a huge opportunity for conservation. Below, we compare the status of tropical forests in different regions of the world, looking at how much of the original forest remains in each region and how “healthy” those remaining forests are. We also examine differences between lowland rainforests, hilly or mountainous forests, and swampy forests in terms of where deforestation has been concentrated, and what remains.

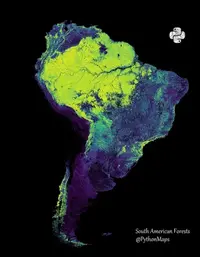

South America: Lungs of the Planet vs. Fragmented Fragments

South America contains the world’s largest tropical forests, including the Amazon Rainforest – often called the “lungs of the planet.” Historically, tropical forests covered vast swaths of South America from the Amazon basin to the Atlantic coast. Today the picture is mixed: the Amazon rainforest still spans multiple countries and retains a high percentage of forest cover, but other South American forests (like Brazil’s coastal Atlantic Forest and the Gran Chaco or Chiquitano dry forests) have been drastically reduced.

- Amazon Basin: The Amazon is by far the largest intact tropical forest in the world. As of 2020, the Amazon region had about 526 million hectares of primary forest remaining. This is roughly 80–85% of the Amazon’s forest cover from the early 2000s (the Amazon lost about 5.5% of its forest between 2001 and 2019)[3]. In terms of original pre-deforestation extent (pre-20th century), the Amazon is estimated to have lost around 15–20% of its forests – meaning roughly ~80% remain, although this remaining forest is now increasingly fragmented along its edges. The Amazon still contains by far the largest contiguous areas of “very healthy” primary forest on Earth. Many core areas of the Amazon (especially in the western Amazon, parts of the Brazilian Amazon, and the Guyanas) are roadless and remain functionally intact. For example, Brazil alone still has over 1 million km² of intact forest landscapes (areas of unbroken primary forest. As of the early 2020s) – the only country in the tropics with that distinction[4]. The Amazon’s sheer size has so far allowed it to maintain large gene flow for wildlife across vast areas, except where human incursions have created barriers. The biggest threats to Amazon forest health are the arc of deforestation along its southern and eastern fringes and new infrastructure (like highways) penetrating its interior. Notably, official and unofficial roads have already reached ~41% of the Amazon’s area, leading to patchy fragmentation. For instance, Brazil’s BR-230 and BR-163 highways have spawned fishbone patterns of deforestation as settlers clear land along these roads[2]. Still, compared to other tropical regions, the Amazon remains relatively contiguous – large swaths are tens of millions of hectares of continuous forest with few internal clearings (especially in remote Amazonian parts of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia).

- Atlantic Forest (Mata Atlântica): In stark contrast to the Amazon, Brazil’s Atlantic Forest on the eastern coast has been almost entirely felled over the past centuries. This rich coastal rainforest originally covered over 130 million hectares along Brazil’s coast and into Paraguay and northern Argentina. Today, only an estimated 12% (or less) of the Atlantic Forest’s original area remains forested, and much of that is in small fragments. In terms of primary forest, only about 9.3 million hectares of old-growth Atlantic Forest remain (roughly 7% of the original)[3]. These remnants persist mostly in mountainous areas, steep slopes, and protected reserves. For example, in Serra do Mar and other coastal ranges, some continuous forest corridors survive where terrain impeded agriculture. But the lowland portions of the Atlantic Forest were the first to go – cleared for cities, sugar plantations, and farms as far back as the 16th–19th centuries. What’s left of the Atlantic Forest tends to be broken into patches (many patches are <50 km²)[5], which greatly undermines ecosystem “health” by isolating wildlife populations. The Atlantic Forest’s situation underscores how flat, accessible forests have been hardest hit – only rugged or less arable areas escaped clearing. Though deforestation has slowed in this region in recent decades, recovery is limited; much “forest cover” in the Atlantic Forest today is secondary growth or eucalyptus plantations rather than intact native forest.

- Other South American Forests: Another significant tropical forest region is the Chocó-Darién along the Pacific coasts of Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador. This is an extremely wet rainforest zone. Originally continuous, the Chocó has seen agricultural encroachment, but it still has about 8.4 million hectares of primary forest remaining in 2020[3]. That is perhaps on the order of ~50% of its original extent (the Chocó’s deforestation has been less severe than the Atlantic Forest’s, partly due to its rugged terrain and high rainfall making it less suitable for large-scale farming). Much of the remaining Chocó forest is contiguous and “healthy,” although new roads and oil palm plantations in Colombia and Ecuador have started to chip away at it.

Overall, South America holds the largest share of the world’s remaining tropical forest, thanks mainly to the Amazon. About 3.86 million km² of intact rainforest remain in South America (as of 2016)[4], which is roughly three-quarters of all intact tropical forest on Earth. However, this macro-level view hides the stark internal contrast: the Amazon basin is very healthy in large core areas, whereas other South American forests (Atlantic, parts of Central America’s extension into northern South America, etc.) are in poor health. Even within the Amazon, the forest “health” is uneven – for instance, eastern and southern Amazonia have many clearings and roads, effectively breaking the forest into smaller units, whereas the western Amazon (bordering the Andes) has massive roadless areas. Lowland vs. mountain: Interestingly, in the Amazon, most of the forest is lowland (<500 m elevation) and that lowland expanse remains mostly forested where inaccessible. In the Andes foothills and mountains on the Amazon’s western edge, there has also been deforestation (as people in Andes regions clear slopes for farms), but much of the steep forested slopes in places like Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia still remain because they are within protected areas or remote. For example, Manu National Park in Peru protects montane rainforest up into the Andes, and large portions are intact. On the whole, South America’s flat, fertile forests (like in southern Brazil, Atlantic coast, and some Andean valleys) experienced the highest deforestation, whereas steep or remote areas (western Amazon headwaters, parts of Guiana Shield, etc.) retain very healthy forests. A clear case is Brazil’s Atlantic Forest: the flat coastal plains were almost entirely converted to agriculture, leaving only the hilly interiors with forest fragments[5]. Conversely, in the Amazon, large flat interior areas remain forested simply because they were historically remote – but as soon as a road appears, those flat areas become targets for logging and farming, leading to rapid fragmentation.

Central America: Mesoamerican Forests in Retreat

Central America (Mesoamerica) once was covered in dense tropical forests from southern Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. This region’s forests have been under pressure for a long time due to agriculture, cattle ranching, and high population growth. Current status: Today, forest cover varies by country – for example, as of 2010, Belize still had about 63% of its land under forest, while Costa Rica had ~46%, Panama 45%, Honduras 41%, Guatemala 37%, Nicaragua 29%, and El Salvador only 21%[6]. These figures include secondary forests and plantations, so the percentage of primary forest would be lower. A regional estimate suggests that only around 14% of Central America’s original habitats remain and much of that is fragmented[5]. In terms of primary rainforest specifically, the Mesoamerican region (southern Mexico to Panama) had about 16 million hectares of primary forest left as of 2020[3]. For context, the original extent of dense forest in this region (pre-modern deforestation) might have been on the order of 70–90 million hectares, so it’s likely that roughly 20–30% of the original forest cover remains. However, that remaining forest is not one big block – it’s broken into several blocks of varying health.

Large “healthy” forest blocks in Central America today include:

- The Maya Forest of northern Guatemala, southern Mexico (Yucatán) and Belize: This is the largest contiguous forest in Mesoamerica, covering parts of the Petén region, the Calakmul Biosphere (Mexico), and Belize’s reserves. Being predominantly lowland flat rainforest, makes this section even more remarkable. This block has on the order of a few million hectares of forest. It is one of the healthier lowland forests in the region, though even here fragmentation is increasing. Approximately 60% of the original habitat remains in the Petén-Veracruz moist forest ecoregion (which includes Petén)[5], meaning about 40% has been lost. The remaining Maya Forest still supports wide-ranging species like jaguars. Yet, roads and slash-and-burn agriculture are fragmenting it; for instance, the Maya Forest is being nibbled away around its edges and by incursions into Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. Still, compared to most of Central America, this lowland forest is in fairly good shape (some large continuous areas >1000 km²). It’s one of the rare cases where a lowland forest on arable flat land has partly survived, likely because it was relatively sparsely populated until recent decades and has some protection status.

- La Mosquitia (Honduras/Nicaragua) and Darién (Panama): These are other significant forested areas. La Mosquitia, straddling Honduras and Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, is a swampy, sparsely populated region – its difficult terrain (wetlands and poor soils) helped preserve forests. Nicaragua’s Bosawás Biosphere Reserve and Honduras’s Río Plátano Reserve form a contiguous forest in this area. However, deforestation is accelerating even there, as cattle ranchers move in. Similarly, the Darién Gap between Panama and Colombia has a large block of forest (connecting to South America’s Chocó). These areas can be considered “healthy” in that they are contiguous and not crisscrossed by major highways (the Pan-American Highway famously has a gap in the Darién). But they are under pressure from planned infrastructure and subsistence clearing. Swampy, flood-prone terrain in these regions has so far limited agriculture, so they act as natural refuges for forest.

- Mountainous Cloud Forests: Central America’s mountains (such as the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, the highlands of Guatemala and Honduras, and Costa Rica’s Talamanca range) once had extensive cloud forests. Many of those highland forests have been cleared or reduced to pockets, especially in places like Guatemala’s highlands and around populated highland valleys. Subsistence farming and coffee cultivation reached high elevations, so only the most inaccessible peaks kept their forests. For example, in the Chiapas montane forests, a significant portion remains on the steep slopes that are protected (formally or by inaccessibility), but lower montane elevations have been converted to farms[5]. Costa Rica’s montane forests are better protected (some in national parks), yet even there, only fragments remain outside parks. Overall, montane forests in Central America have fared better than lowland forests in terms of percent remaining, because many mountain areas were less suitable for large-scale agriculture. But they are often smaller in area to begin with, and heavily fragmented. One analysis noted that in a Costa Rican seasonal montane forest ecoregion, only one-third of the original habitat remains, in very fragmented patches. In contrast, the lowland Caribbean forests of Nicaragua/Costa Rica (Isthmius-Atlantic forests) had more remaining cover (though fragmentation is increasing there too)[5].

Overall deforestation pattern in Central America: Lowland tropical forests that were on fertile flat ground (especially Pacific coastal plains and volcanic highlands) were the first to be cleared for agriculture centuries ago (e.g., Pacific coast of Guatemala/El Salvador for coffee, sugar, cattle; central valleys of Costa Rica for settlement). The areas that remained forested longer tended to be those that were either too remote, too swampy, or too rugged – such as the Caribbean mosquito coast (swampy), parts of the Yucatán (historically underpopulated after Mayan collapse), and mountain ranges. Even those refuges are now under threat as population and development increase. Central America now has a high density of roads relative to its forest area, which has led to severe fragmentation. For instance, one study found that a Central American moist forest ecoregion had the highest density of roads and forest edges among regional comparisons, indicating extremely fragmented remaining forest patches[5]. In many countries (e.g., Guatemala, Honduras), remaining forests are largely confined to protected areas, and even within some parks illegal logging occurs.

Thus, forest health in Central America is generally poor except in a few key refugia. Where large blocks remain (Maya Forest, Mosquitia, Darién), they are often dissected by encroachment from the edges rather than by highways through the middle (since highways are relatively few). These forest blocks remain contiguous at their core but continue to shrink along their edges. In contrast, smaller countries like El Salvador have almost no large forest blocks left at all (El Salvador’s primary forests are <2% of its land)[7].

Lowland vs. upland vs. swamp comparison: Central America illustrates a trend seen elsewhere: lowland forests on fertile soil were cleared first, while poorly drained swamps and steep highlands tended to survive longer. For example, nearly all flat lowland rainforest outside protected areas in Pacific Nicaragua and Costa Rica is gone, but seasonal swamp forests in the Caribbean coastal lowlands still exist (though threatened)[5]. Similarly, upland pine-oak forests and cloud forests in many areas were logged or farmed on gentler slopes, but the highest, roughest peaks kept some forest. The ratio of deforestation lowland:upland is high – a much larger percentage of lowland rainforests have been lost in Central America compared to montane rainforests. However, in populated upland regions (like the Guatemalan highlands), montane forests were also extensively cleared for agriculture (in those cases, being mountainous did not save the forest if the climate and soils were suitable for crops like coffee or potatoes). So the pattern is nuanced: it’s really “suitable for agriculture” vs “unsuitable” that matters. Many mountain areas are unsuitable (hence forest remains), but where they were suitable (volcanic highlands), they were cleared early.

Consider the following articles for a more in-depth review of the remaining forests and wilderness areas of Costa Rica and Panama.

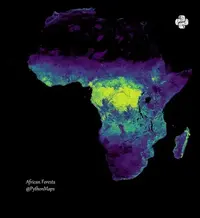

Africa: A Continent of Contrasts – West African Losses and Central African Strongholds

Africa’s tropical forests are chiefly in two regions: West Africa (the Upper Guinean forests and Nigeria-Cameroon) and Central Africa (the Congo Basin, plus some in East Africa and Madagascar). Historically, these forests covered a large area across the equatorial belt and coastal West Africa. Today, their status varies dramatically by sub-region:

- West Africa: This is one of the most deforested tropical regions on Earth. Countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone once had extensive lowland rainforests. According to the World Resources Institute, over 90% of West Africa’s original rainforest is now gone[8]. What remains is heavily fragmented and degraded. For example, it’s estimated that across the Upper Guinean forest region (which spans Guinea to Togo), only about 10% of the original dense forest cover remains[9]. In many West African countries, deforestation happened early (19th and 20th centuries) for plantations (cocoa, palm oil) and timber. The remaining forests are often small patches in protected areas or along national borders where low population density provided some respite. The Earthdata/USGS analysis notes West Africa’s forests are “one of the most critically fragmented regions on the planet”[9]. For instance, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have very little intact forest outside a few parks (e.g., Taï National Park in Côte d’Ivoire, Kakum in Ghana). Nigeria, which had rich rainforests in the southeast, has lost almost all of them except in Cross River State on the Cameroon border. In fact, large intact forest tracts in West Africa remain only in parts of southeast Côte d’Ivoire and the Nigeria–Cameroon border area. Those areas correspond to regions like Taï (Côte d’Ivoire) and the Cross River – Korup Park area (Nigeria/Cameroon). The mention of “watersheds along the border of Nigeria’s Cross River State and Cameroon”[8]highlights that one of the last big blocks straddles that frontier (a region of hilly terrain and lower human density). West Africa’s forest “health” is thus very poor – even the remaining forests are often isolated fragments <1000 km² and impacted by hunting and logging. For example, only 69,000 km² of Upper Guinean forest remains and much of that is degraded by logging[9]. The fragmentation means many species (like forest elephants, primates) have highly restricted habitats and disrupted migration routes.

- Central Africa (Congo Basin): In contrast to West Africa, Central Africa still retains a vast expanse of contiguous rainforest – the second largest on Earth, after the Amazon. The Congo Basin rainforest spans parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Republic of Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), and Equatorial Guinea. DRC alone contains about 60% of Central Africa’s forest cover. As of 2020, the Congo Basin had about 168 million hectares of primary rainforest remaining[3]. This represents the bulk of the original extent; tropical Africa as a whole has lost about 22% of its forest area since 1900, meaning roughly ~78% remains continent-wide[3] – but that loss was not evenly spread (most occurred in West Africa, whereas Central Africa remained more intact until recently). One study using satellite data estimated that just under 70% of Congo Basin forests are still “fully intact” (showing no signs of fragmentation or degradation), down from about 78% intact in 2000[11]. In other words, around 30% of the Congo forest has some level of disturbance or fragmentation, but 70% remains as large blocks – a high figure compared to other regions. Indeed, central Africa contains some of the largest roadless tropical forests left. For example, northern DRC and neighboring Congo/Gabon have millions of hectares with no major highways. This is why Africa as a whole still has about 0.84 million km² of intact rainforest (mostly in the Congo Basin) as of 2016[4]. Historically, deforestation in the Congo was kept low by factors like conflict, poor infrastructure, and low development – up until the 2000s, deforestation rates in the Congo Basin were far lower (on a percentage basis) than in the Amazon or Southeast Asia. For instance, between 2002 and 2019, the Congo Basin lost about 3.5% of its 2001 primary forest cover, compared to 6.6% in the Amazon and much higher rates in Southeast Asia. This indicates that most of Central Africa’s forest is still “healthy” in the sense of being contiguous. However, the situation is changing: deforestation in the Congo Basin is trending upward, with new logging roads and agriculture expanding, especially around the peripheries of the intact core[3].

- Other African tropical forests: East Africa has smaller pockets of tropical forest (e.g., coastal forests of Kenya/Tanzania, montane forests in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and eastern DRC’s Albertine Rift). Many of these have been heavily deforested as well, due to high rural population densities. For example, the montane rainforests in Rwanda and Burundi were mostly converted to agriculture, leaving only parks like Nyungwe or volcano summits forested. Uganda’s tropical forests (outside a few parks like Bwindi and Kibale) have also shrunk greatly. These areas are a tiny fraction of Africa’s forest by area, but biologically important. Generally, East African tropical forests (montane or coastal) are in poor shape (often <30% of original remain). Madagascar, as mentioned, has lost roughly 90% of its eastern rainforests; the remaining forests are mostly along the eastern escarpment and some in the northwest, but largely fragmented.

In summary, Africa’s tropical forest health shows a sharp West-to-Central gradient: West Africa is an example of near-total deforestation of lowland rainforests, whereas Central Africa still has immense intact forests. Why the difference? West Africa’s forests were in relatively accessible coastal zones with long histories of agriculture (including European colonial plantations), and many West African forests were on flat, arable land (cocoa and palm thrive in former forest soils). Meanwhile, the Congo Basin, though also mostly lowland, had logistical barriers (the sheer size, rivers, political instability) that delayed intensive exploitation. Additionally, some Congo forests sit on peaty swamps (like the Cuvette Centrale in DRC) which are difficult to clear – those swamp forests remain almost entirely intact since they’re “unfit” for conventional agriculture. The Likouala peat swamp region in DRC/Congo, for example, is one of the largest tropical peatland complexes and is still largely pristine due to its inaccessible, flooded nature. This mirrors the trend of swampy areas serving as refuges: what fertile terra firme land in Central Africa has been cultivated tends to be around villages, roads, or the forest-savanna edges, but the huge swamp forests in the inner Congo basin have been a safe haven for intact forest and wildlife.

Lowland vs. Mountain in Africa: Interestingly, in Africa many mountain areas were deforested early in certain regions. Unlike in Asia or the Americas, African human settlement often favored highlands (because of cooler climate and fewer disease vectors like tsetse flies). For example, the Ethiopian Highlands and Kenyan Highlands were largely cleared of their Afromontane forests for agriculture centuries ago – these regions are outside the main rainforest belt but exemplify that mountainous terrain did not guarantee forest survival if the land was tillable. In the core tropical zone, West Africa’s only significant highlands with rainforest (e.g., Guinea highlands, and highlands of Cameroon) also experienced deforestation since even hilly areas were used for crops like coffee, cocoa, or timber extraction. Meanwhile, Central Africa’s highlands (like eastern DRC and Rwanda) were heavily settled and thus deforested (only steep mountain parks like Virunga or Kahuzi-Biega keep some forest). On the other hand, Central Africa’s lowlands remain mostly forested, showing that accessibility and development, not elevation, were the key drivers in that region. So Africa doesn’t show a simple lowland-vs-upland difference in forest loss – it’s more about region-specific human pressures. West African lowlands were ravaged, whereas Central African lowlands were comparatively spared until recently. In West Africa, what little remains is often in protected areas that sometimes coincide with uplands (for instance, upland areas of Sierra Leone or the Sankaranaran Massif in Guinea host some forest patches because they were less accessible).

In terms of numbers: Africa’s tropical forest originally (pre-1900) might have been around 3.5–4 million km². Today, the tropical African rainforest is about 2.8–3.0 million km². Most of that is the Congo Basin; West Africa’s remaining rainforest is only on the order of 70,000 km² (for Upper Guinea) plus perhaps another ~100,000 km² if you include Nigeria/Cameroon’s share, totaling well under 200,000 km² in West Africa – a tiny fraction of what once was. Central Africa by contrast has millions of km² still under forest. The Congo Basin remains one of the last places with extremely large contiguous primary forests – for example, the tri-national park complex of Nouabalé-Ndoki (Congo Rep), Lobéké (Cameroon), and Dzanga-Sangha (CAR) links with surrounding forests to form an intact landscape of thousands of square kilometers. Gabon has protected most of its intact forests with a robust park system, keeping its forest cover ~85% of land area. But new forces like industrial agriculture (palm oil, rubber) and logging concessions threaten to fragment these forests much like what happened in the Amazon and Southeast Asia.

Swamps and mangroves: Africa has significant mangrove forests along coasts (e.g., Nigeria’s Niger Delta, Guinea-Bissau). These often fall outside “contiguous interior forest” discussions but are worth noting: West African mangroves have also been cut for rice farming and fuelwood, though some large areas remain (e.g., the Sundarbans-like mangroves of the Niger Delta). Mangroves are typically not counted in the rainforest statistics, but they are another case where swampy, tidal conditions provided partial protection. Still, Nigeria lost a lot of mangrove to oil and development. Central African coasts (Cameroon, Gabon) still have intact mangroves in many areas.

In summary, Africa’s tropical forests show that human factors (population, infrastructure, policy) dictate forest health more than just geography. West Africa’s forests, on flat fertile ground, were decimated (healthy forests remain only in a few refuge spots, often upland or protected). Central Africa’s forests, though also mostly flat, stayed healthy longer due to lower development – but as that changes, even these will face fragmentation (for instance, new roads in DRC could potentially split what were once single huge forests into multiple smaller ones, with all the ecological consequences that entails). Conservation efforts in Africa focus on keeping the Congo Basin’s forests intact as one unit, to avoid repeating West Africa’s fragmentation scenario. Currently, the Congo Basin is still one contiguous forest block stretching across several countries[3], which is positive for gene flow and species like forest elephants and great apes that roam large distances. But the coming decade will test whether that contiguity can be maintained.

Asia: Heavy Losses in Southeast Asia, Last Stands in Mountains and Islands

Asia’s tropical forests (largely in South and Southeast Asia) have experienced some of the fastest and most widespread deforestation in the past century. The region includes the immense rainforests of Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, India’s Northeast, and smaller pockets elsewhere. These forests are incredibly biodiverse (Southeast Asia’s dipterocarp forests, for example, rival the Amazon for species richness in some taxa) but have been under intense pressure from agriculture (especially oil palm, rubber, rice) and logging.

Current status: Tropical Asia (including Southeast Asia and South Asia’s tropics) has lost a higher fraction of its original forests than any other tropical region. As noted earlier, only ~7% of the world’s remaining intact tropical forest is in Asia[1] – a strikingly low share given that historically Asia had vast rainforests. This reflects how much has been destroyed or degraded. A Rainforest Foundation Norway report highlighted that, for example, on the island of Sumatra, only 9% of the original rainforest remains in an intact condition[1]. Similarly, large portions of Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia have been deforested or logged. However, some significant forest blocks remain on the large islands (Borneo, New Guinea) and in certain highlands or remote areas.

Let’s break down by sub-region:

- Sundaland (Indonesia/Malaysia: Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Malay Peninsula): This was once a continuous rainforest region. Today it’s the epicenter of tropical deforestation. For instance, Borneo (shared by Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei) has lost roughly half of its forest cover just since the 1970s. In the mid-1980s, about 75% of Borneo was still forested; by recent years, only about 50% of Borneo’s original forest remains. And much of what remains is degraded by logging. A detailed study indicated that by 2015, 28% of Borneo’s land area was still primary (old-growth) rainforest and another ~22% was secondary or logged forest – totaling ~50% forest cover[3]. The rest has been converted mainly to oil palm plantations or other uses. Crucially, the lowland forests of Borneo – especially in coastal areas of Malaysian states (Sabah, Sarawak) and Kalimantan – have been hardest hit. For example, in Sarawak (Malaysian Borneo), only 18% of the original lowland forests remained intact as of 2010[12]. Borneo’s surviving intact forests are now largely in the interior mountainous regions (the Heart of Borneo area straddling Indonesia and Malaysia) and some protected areas. As of 2020, about 51 million hectares of primary forest remained in Sundaland (Borneo, Sumatra, etc.). This primary forest area is less than one-quarter of the region’s original forest extent. Sumatra in particular has been devastated by logging, palm oil, and pulpwood plantations – it lost 25% of its primary forest just from 2001–2019, and much more before that. Now Sumatra’s remaining forests are mostly confined to the mountainous spine (e.g., Gunung Leuser ecosystem) and a few lowland pockets like Tesso Nilo (which are under threat). Peninsular Malaysia and Thailand have also seen huge declines in lowland forest; for instance, Peninsular Malaysia lost 14% of its primary forest 2001–2019[3], and historically much of its lowlands were converted to rubber and oil palm. Only the steep highlands (like Taman Negara region, parts of the Main Range) still hold large forest blocks in Peninsular Malaysia. Java, once lush, is almost entirely deforested except small highland parks – an example of a tropical island where fertile volcanic soils led to >90% deforestation long ago.

- Indo-Burma (Mainland Southeast Asia – Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, NE India): This region’s forests have been fragmented over a longer period due to dense human populations. Large areas of Thailand and Vietnam were cleared in the 20th century (Vietnam’s war era also saw forest destruction). What remains tends to be in remote mountainous areas or along the Mekong headwaters. As of 2020, the Indo-Burma region had about 40 million hectares of primary forest remaining. Much of that is in Myanmar and Laos, which have the biggest contiguous forests in mainland Southeast Asia. Myanmar alone accounts for ~34% of the region’s primary forest cover – particularly in northern Myanmar (Hukawng valley, etc.) and along the Thai border (Tenasserim). Laos also retains forest in its mountains (19% of region’s primary). Cambodia and Vietnam have less – Cambodia’s deforestation in the last two decades has been rampant; it lost over 28% of its primary forest just since 2001[3], largely for rubber and other plantations, meaning its original forest cover is greatly diminished (Cambodia’s total forest cover is now under 50%, much of that secondary). Thailand has some well-protected parks (e.g., Western Forest Complex) but vast areas were lost historically. Overall, maybe on the order of 20–30% of Indo-Burma’s original dense forest remains, and what remains is heavily fragmented except in a few landscapes (e.g., large contiguous forests still exist along the Myanmar-Thailand border and parts of northern Myanmar/Yunnan border). Many surviving forests are in uplands or border areas that were less accessible.

- Papua New Guinea & Indonesian Papua (Island of New Guinea): New Guinea is often grouped with Asia or Oceania. It holds one of the last great tropical forests. The entire island of New Guinea (split between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia’s Papua provinces) has around 248,000 km² of intact rainforest as of 2016[4]. In 2020, New Guinea had about 64 million hectares of primary forest remaining[3] – which is roughly 90% of its original forest cover. This makes New Guinea’s forests among the healthiest in the tropics. Deforestation is relatively recent and limited there, though accelerating. Between 2002 and 2019, Indonesian Papua lost only ~1.8% of its primary forest, and PNG lost ~2.2%. So roughly 97–98% of New Guinea’s primary forests were intact as of 2019, an astonishingly high percentage compared to other regions. New Guinea’s forests span coastal mangroves, lowland rainforests, and extensive montane cloud forests in its central cordillera. Much of this forest is contiguous and roadless (especially in PNG and the Indonesian highlands). The Australasian realm (New Guinea & northeastern Australia) had the second-lowest rate of forest loss among major tropical areas since 2000. The forests in New Guinea are still very healthy, but they face future threats from logging and industrial farming (palm oil expansion is starting in Papua). It’s notable that virtually all of this region’s primary rainforest is on New Guinea – Australia’s tropical forests are minimal by comparison[3].

- Other Asian tropical forests: India and Bangladesh have some tropical forests, like the Western Ghats (in south India), Northeast India’s rainforests, the Sundarbans mangroves, and the Andaman/Nicobar Islands. These have mostly been reduced or degraded as well. For example, the Western Ghats have under 30% of their original forest left (with some good protected areas like Periyar or Silent Valley amid tea and coffee plantations). Northeast India (Assam, Arunachal, etc.) still has significant forest cover in parts of Arunachal Pradesh (some of which is contiguous with Myanmar’s forests) – the Eastern Himalaya foothills are a biodiversity hotspot, and Arunachal’s Eastern Himalayan forests are relatively intact in some districts (one estimate is ~15,500 km² intact there[4]), but lower altitude areas have seen tea plantations and jhum (shifting cultivation) clearing. The Philippines is another story of massive deforestation – from ~90% forested a few centuries ago to only ~20-25% forest cover today, and much less primary forest (only a few% primary remains in some islands). Sri Lanka similarly retains only fragments of its lowland rainforests (e.g., <10% remains in the wet zone).

Overall, Southeast Asia (excluding New Guinea) has probably 20% or less of its original primary forest remaining intact. As a whole, Asia’s tropics have seen forest loss and degradation on a greater scale (relative to original area) than Amazonia or Central Africa. For instance, one-third of Asia’s tropical rainforest biome is completely gone and another one-third is degraded according to global estimates[1]. The remainder is mostly in New Guinea and a handful of pockets elsewhere.

Drivers and patterns: Southeast Asia’s deforestation was initially concentrated in lowland areas – the rich lowland dipterocarp forests were logged for timber and cleared for agriculture (rice in Thailand and Vietnam deltas/plains, oil palm and rubber in Malaysia/Indonesia, etc.). Because lowlands are easier to access and often have richer soils, they were deforested first. For example, in the 2000s, the majority of forest loss in SE Asia occurred in low elevations. By the 2010s, however, the frontier of deforestation had shifted to higher elevations as lowland areas became saturated with agriculture. A recent study found that by 2019, 42% of annual forest loss in Southeast Asia was happening in mountainous regions, up from much lower percentages in 2000. This means farmers and plantations have increasingly moved into hill country, despite steeper slopes and thinner soils – a sign that lowland arable land is running out in places like Indonesia and Myanmar. This upslope march of deforestation is particularly notable in parts of Sumatra, Borneo, and mainland Southeast Asia’s highlands. Previously, one might have considered rugged interior highlands (like Borneo’s interior or Myanmar’s Shan hills) relatively safe, but now those are being cleared too. Scientists were surprised to see such accelerated forest loss in mountains that were once thought protected by their remoteness[13].

Swamp and peat forests: Southeast Asia also has extensive peat swamp forests (especially in Sumatra, Borneo, peninsular Malaysia) and mangroves. Historically, these waterlogged forests were spared during early waves of deforestation because they are hard to cultivate. However, in recent decades even these have been targeted – for example, large tracts of peat swamp in Sumatra and Borneo have been drained for oil palm or pulpwood. The Mega Rice Project in the 1990s tried (disastrously) to convert Borneo’s peat swamps into rice fields, causing massive fires. Still, some peat forests remain (e.g., parts of Sabangau in Borneo, or Sumatra’s Alas River swamps) – though they are often degraded by logging canals. Mangrove forests in Southeast Asia (like in Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand) have been cleared extensively for shrimp aquaculture and coastal development. It’s estimated Southeast Asia has lost 25–50% of its mangroves in the last 50 years. But large mangrove stretches still exist in e.g. Indonesia (the world’s largest mangrove area, though declining) and the Sundarbans shared by India/Bangladesh (the latter being the world’s largest intact mangrove forest). These swampy forests count as “forests unfit for agriculture” that have survived longer by virtue of their inaccessibility – for example, the Sundarbans mangroves survived because they are too wet and salty for farming, and are now partly protected.

Fragmentation: Southeast Asian forests are highly fragmented by roads and plantations. In Borneo and Sumatra, logging roads penetrated deep into forests since the 1970s, and now what remains are often patchwork landscapes. Truly road-free areas are scarce outside of central Borneo and parts of Papua. Wildlife corridors are broken – e.g., in Sumatra, elephants and tigers are now confined to separated national parks in many cases, with plantations in between. In Peninsular Malaysia, a major highway (the Gerik highway) splits the Taman Negara forest complex, though wildlife crossings are being attempted. In India, almost all forests are within a few kilometers of human settlement or roads. So the concept of large “healthy” blocks is mostly limited to a handful of places like the Heart of Borneo, parts of New Guinea, Northern Myanmar, and some Thai/Myanmar border forests. Asia’s tropical forests have the highest fragmentation metrics overall among tropical regions.

A stark stat: on Sumatra, only 9% of original rainforest remains truly intact (undisturbed)[1]. The rest is either gone or broken up. Similarly, on Borneo, only about 25% of the island’s original forest remains in intact condition according to some reports[14] (the difference between the ~50% forest cover remaining and ~25% intact suggests half of what’s left is degraded forest).

Lowland vs. Mountain vs. Swamp in Asia: The pattern is clear – fertile lowlands were nearly completely converted. For example, the Javan lowlands, Sumatran and Malaysian lowlands (for palm oil and cities), Thai and Vietnamese deltas and plains (rice), Indian Indo-Gangetic plains (agriculture) – all these were once forested but were prime targets for human use and thus mostly lost. Mountains and uplands – for example, Borneo’s interior highlands, the Annamite Range in Laos/Vietnam, the Tenasserim hills – remained forested longer, serving as refugia. Now they are the sites of last stands for many species (e.g., the Annamites harbor rare animals like saola in remaining forest because the lowlands of Vietnam are almost entirely farmed). However, as noted, these highland forests are now under attack as well, and their steepness is no longer a guarantee of protection[13]. Swamps/peat – for a while, they were left alone, but recent decades saw aggressive draining. Still, some remote peat forests (like parts of West Papua’s Asmat region, or parts of southern Borneo’s swamps) remain because even large companies find them challenging. Those that remain, though, are often one governmental decision away from destruction (e.g., Indonesia at times has moratoria on developing peatlands due to carbon considerations).

In summary, tropical Asia’s forest health is generally the worst among the tropics, except for the special case of New Guinea and some pockets. Most countries in South/Southeast Asia have only scraps of primary forest left outside protected areas. The region exemplifies how human density and economic development can overwhelm even biodiverse forests. The only silver lining is that some countries (like Vietnam, China, India) have seen recent net gains in tree cover through reforestation, but much of that is plantations or secondary forest of limited biodiversity value. The conservation focus is on saving what primary forests remain (especially in Indonesia, PNG, Myanmar) and restoring connectivity where possible (wildlife corridors in places like Thailand-Malaysia). If current trends continue, the lowland rainforests on fertile ground in Asia could essentially vanish, leaving only higher elevation or waterlogged forest islands.

Australia and Oceania: Last Refuges in the Australasian Tropics

Australia is generally not known for vast tropical rainforests – most of Australia’s interior is dry. However, the northeastern tip of Australia (Queensland) does extend into the tropics and once supported lush rainforests (e.g., the Wet Tropics of Queensland). Additionally, Oceania’s islands, particularly New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and others, have tropical forests. For our purposes, we consider the “Australasian” tropical forests which include New Guinea (often grouped with Asia but biogeographically distinct) and northern Australia, plus nearby Pacific islands.

- New Guinea (PNG & Indonesian Papua): As discussed above in the Asia section, New Guinea is a critical stronghold of intact tropical forest. It can be considered part of the Australasia region. It has one of the highest percentages of original forest remaining – roughly 90% of New Guinea’s original forest is still present, and much of it intact. This includes extensive lowland rainforests along the coasts and in the river basins (Fly River, Sepik, Mamberamo, etc.) and mountain forests over its central ranges (some peaks over 4,000 m have montane forests and even alpine grasslands above treeline). Development in New Guinea has been limited compared to Asia: Papua New Guinea has seen logging along accessible rivers and roads, and subsistence gardening by communities, but large swaths remain roadless. Indonesian Papua similarly had very low deforestation until the 2000s when some palm oil projects began. The Australasian realm had the second-lowest rate of primary forest loss since 2001 among major rainforest regions. For example, from 2002–2019, PNG lost only ~0.7 million ha of primary forest (2.2% of its 2001 cover). So New Guinea’s forests are very healthy overall – big contiguous blocks, minimal fragmentation in the interior. Culturally, a lot of New Guinea’s interior forests are managed by indigenous communities with relatively low-impact use (hunting, small-scale sago harvesting, etc.), which has helped maintain them. That said, mining and logging operations in certain areas (e.g., Ok Tedi mine area in PNG, or logging concessions in lowland Papua) have created localized deforestation and road networks. Conservationists consider New Guinea “the last frontier” for tropical timber and plantations – and there is a push to avoid repeating the massive deforestation of Borneo/Sumatra there[3].

- Australia (Queensland’s Wet Tropics and NT): The Australian continent itself has limited tropical rainforest. The main area is the Wet Tropics of Queensland, a strip on the north-east coast. This forest is actually a World Heritage Site now, recognizing its unique biodiversity (ancient lineage rainforest flora). However, it’s relatively small (on the order of 900,000 ha of forest). Much of the original lowland rainforest in Queensland was cleared in the 19th–20th centuries for agriculture (sugar cane, dairy). Today, about half of the original Wet Tropics rainforest remains, mostly in uplands and protected areas. For example, the Atherton Tablelands and coastal plains were largely cleared; remaining forests are on mountainous terrain like around the Daintree River and the slopes of the Great Dividing Range. Overall, Australia’s tropical rainforest is highly fragmented but now largely protected – what’s left is “healthy” in protection but isolated. Elsewhere in northern Australia, the climate is more monsoonal savanna, not closed rainforest, though there are pockets of monsoon vine thickets and gallery forests. Those have also been impacted by grazing and introduced species but less is known globally as they are comparatively small.

- Pacific Islands: Many Pacific islands just outside the strict tropical zone have tropical-like forests (Fiji, Samoa, etc.) which have seen deforestation for agriculture and logging. For instance, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu still have significant forest cover (Solomons have had heavy industrial logging though, reducing primary forest). These islands often have mountainous interiors that kept forest cover. The Solomon Islands and nearby Melanesian islands are sometimes grouped with the Australasian forests in analyses (the RFN report listed “Melanesia (PNG, Indonesian Papua, Solomon Is., Vanuatu)” as having about 264,500 km² intact rainforest as of 2016[4], which includes New Guinea’s huge contribution). The Solomon Islands themselves have lost large portions of accessible lowland forest to commercial logging, though some interior and smaller islands’ forests remain.

In terms of percent remaining relative to original: New Guinea and many Pacific islands had deforestation start later (mid/late 20th century) so they often still have a large fraction remaining. PNG’s forest cover is still ~70% of land area. Solomon Islands historically were heavily forested; they might still have perhaps 50-60% forest cover, albeit being rapidly logged. Fiji has lost more (a lot converted to agriculture, mahogany plantations, etc., possibly ~50% loss).

Lowland vs. Mountain in Australasia: The pattern holds: in New Guinea, lowland forests along accessible rivers have been logged more (e.g., along the Sepik or Ramu in PNG, or near the coast in Papua’s Merauke region being cleared for agriculture), whereas mountain forests in the highlands remain almost entirely intact (partly because infrastructure doesn’t reach many high-altitude areas). Papua New Guinea’s Highlands have some deforestation around populated valleys (for subsistence gardens), but steep mountain slopes remain forested, and there are no highways crossing the central ranges outside a few spots. In Queensland, as noted, lowland rainforest was cleared for cane fields, leaving mostly upland forest intact. So again, fertile flat areas were taken, rugged/wet ones were spared.

Swamps: New Guinea has enormous swamp forests in the south (Trans-Fly and Papuan south coast) – these are largely intact (some logging along rivers aside). These peat swamps and floodplain forests are an example of “unfit for agriculture” terrain that remains as healthy forest.

Therefore, Australasia (especially New Guinea) currently harbors some of the most intact tropical forests in the world. The key will be keeping them that way by managing new development. New Guinea and neighboring Melanesian islands are essentially in the stage where the Amazon and Congo were maybe 40-50 years ago – largely intact but on the cusp of greater exploitation.

Lowland vs. Upland vs. Swamp: Patterns Across the Tropics

Looking across all tropical regions, a clear trend emerges: deforestation has disproportionately targeted lowland, flat, and fertile forests, whereas steep mountainous forests and waterlogged swamp forests have survived at higher rates. However, this trend varies in strength across regions and is starting to change as remaining land becomes scarce.

-

Lowland/Flat Forests: These are the rainforests on plains or gentle hills – historically the most biodiverse and most carbon-rich forests (e.g., Amazon lowlands, Borneo lowlands, Congo Basin terra firme). They were also the easiest to clear for agriculture or pasture. Consequently, in places with high population or agricultural value, lowland forests are largely gone. For example, West Africa’s lowland rainforests have been almost completely converted to farms and plantations (over 90% gone)[8]. Southeast Asia’s lowland forests (Sumatra, Java, lowland Philippines, lowland Thailand/Vietnam) are overwhelmingly gone or degraded – these areas now host cities, rice fields, and plantations. Even in the Amazon, which still has much lowland forest, deforestation is concentrated in the low elevation fringes (e.g., along the southern “arc of deforestation” where soils are fertile). The fact that the Amazon interior still has forest is more due to historical inaccessibility than terrain – whenever roads appear, the flat Amazon forest tends to be rapidly felled up to a certain distance from the road[2]. In Central America, low coastal plains and interior valleys were cleared early, versus some mountain slopes that retained forest.

In quantitative terms, a recent global analysis (Chen et al. 2024) found that in over 65% of the world’s mountain regions with forests, the majority of forest loss has occurred at low elevations (the foothills), rather than higher up[15]. This highlights that even within mountains, humans deforest the lower, gentler parts first. Low elevation areas often have better soils and access, so they get converted and the higher slopes become the last refuge.

Ecological impact: The loss of lowland forests is critical because those areas often harbor unique biodiversity (many tree species and large animals prefer lowlands) and serve as corridors between highlands. When lowlands are cleared, remaining highland forests become “islands” of habitat, isolated from each other. For instance, in tropical Asia, many mountain national parks are now isolated because the connecting lowlands are gone – meaning species cannot migrate between mountain ranges easily.

-

Hilly/Mountain Forests: Terrain with steep slopes, high elevations, or rugged topography tended to be cleared later or sometimes not at all, especially if soils were poor or climate cooler. Thus, many countries exhibit a pattern where forest cover remains higher in mountains than in adjacent lowlands. For example, in Madagascar, the lowland rainforests were almost entirely replaced by farms, but some montane rainforest on steep slopes survived a bit longer (though Madagascar’s case is extreme with both gone to a large degree). In Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, the inland mountain ranges still have forest fragments whereas flat coastal areas do not[5]. In the Congo Basin, mountains per se are not widespread, but areas with difficult terrain (e.g., ravines, rocky areas) also saw less deforestation – plus, important to note, many Bantu agricultural societies in Central Africa historically avoided dense rainforest interiors and higher altitudes in favor of mixed savanna environments, leaving a lot of the forest (flat or not) intact until modern times. Conversely, in East Africa (Uganda, Rwanda), fertile volcanic mountain soils were very attractive to farmers, resulting in mountain forests being cleared despite steepness – demonstrating that if population pressure is high enough, even rugged land gets used.

A worrying modern trend is that as lowlands have been exhausted, deforestation is advancing into mountains. The Mongabay study on Southeast Asia found that by the 2010s, deforestation was accelerating in upland areas that were previously spared. The frontier is moving upslope ~15 meters per year in elevation in SE Asia[13]. Similar patterns may occur in Amazonia if lowland areas continue to be occupied – eventually, pressure could mount to develop even hillier terrain that was once seen as marginal. Already in the Andes (e.g., in Colombia or Peru), farmers have cleared cloud forests on mid-slopes for crops like coffee.

Mountain forests tend to remain more contiguous and “healthy” until very late in the deforestation process, since human impacts creep up the slopes gradually. This means many mountain ranges still have large intact forest blocks (e.g., the Central Cordillera of New Guinea, the Sierra Madre of the Philippines had until recently, parts of the Albertine Rift mountains in DRC, etc.). These serve as refuges for wildlife that can’t survive in farmlands below. However, mountain forests are not immune to fragmentation – roads and mining can cut into them too. A striking example is the construction of roads into formerly roadless mountains of Laos, Myanmar, and New Guinea, now opening up those forests. The difference from lowlands is that often only one or two roads might exist, but even one road can effectively split a forest and allow settlers to penetrate.

Another aspect is microclimate: mountain forests often are cooler and wetter; climate change and upslope species migrations make it vital to keep connectivity from lowlands to highlands. If lowland forest is gone, species trying to move uphill as temperatures rise might have nowhere to go – a critical issue for climate resilience of biodiversity[13].

-

Swamp and Mangrove Forests: These are forests on waterlogged soils – peat swamps, floodplains, mangrove tidal forests. Historically, such areas were considered unsuitable for traditional agriculture (too wet or flood-prone) and even for settlement (disease-infested swamps discouraged colonization). As a result, swamp forests often survived longer than nearby dryland forests. For example, in the Congo Basin, vast swamp forests along the Congo and Ubangi rivers remain virtually intact today – they are some of the least disturbed tropical forests on Earth. Likewise, Peru’s Amazonian swamps (Pacaya-Samiria) and Brazil’s Varzea floodplain forests, though selectively logged, still exist over large extents. Mangroves fringed tropical coasts and were largely intact until the mid-20th century when shrimp farming and coastal development ramped up – even now, around 67% of global mangroves remain (one-third lost), which is better than the ~50% loss of overall tropical forests. So in many countries we see that swamps were the “last to go”: e.g., in Sumatra, after most dryland forest was gone, companies moved into peat swamps; in West Africa, after upland forests vanished, some coastal mangroves like in Guinea-Bissau were still intact (but now threatened by rice polders or salt works).

That said, the calculus is changing – modern technology and economics have made even swamps exploitable. Draining peat swamps for oil palm or pulp plantations is now common in Indonesia and Malaysia. Mangroves are cleared by bulldozers for aquaculture in Asia and by urban expansion in Africa and the Americas. The result is that these formerly protected-by-nature forests are rapidly shrinking. For example, Indonesia has drained huge areas of peat forest in Kalimantan and Sumatra (leading to massive carbon emissions and fires). West African mangroves in Nigeria have been cut for rice fields and infrastructure, though some areas remain. Still, proportionally, one could say a higher percentage of swampy forest remains globally compared to equivalent fertile dry forest, simply because not all swamps have been targeted yet or some are being conserved due to recognition of their ecosystem value (e.g., Ramsar wetlands).

Gene flow and fragmentation: Swamp forests often act as barriers for humans but highways now sometimes cut even through them (with causeways). If a major road does slice through a swamp forest, it fragments it much like any other. But many swamp forests are linear (along rivers) so fragmentation is more about outright conversion than internal division.

-

Fragmentation and “Forest Islands”: One consequence of the differential deforestation of lowlands vs uplands is that we often see small island-like forests remaining in mountains or swamps, separated by large cleared areas. For example, in West Africa, parks like Ghana’s Kakum (in a semi-hilly area) or Côte d’Ivoire’s Taï (somewhat upland) are isolated amidst farmlands – effectively biodiversity islands. In Southeast Asia, an island of forest like Khao Yai in Thailand (on a plateau) or Kerinci Seblat in Sumatra (mountains) stands isolated from other forests by vast stretches of agriculture. This fragmentation severely limits wildlife movement – a forest-bound species might be stuck in one “island” and at risk of inbreeding and local extinction if the patch is too small. As the user pointed out, a highway turning one large forest into two smaller ones can “eliminate gene flow of small to large animals” – an example being how Malaysia’s new East Coast Highway, if not mitigated, could separate tiger populations in Taman Negara from those in the Main Range.

In numbers, less than 36% of tropical rainforests globally remain intact (as large contiguous areas)[1], and the rest are fragmented to varying degrees. Even in the Amazon, where overall forest cover is high, fragmentation is creeping in – with an estimated ~41% of the Brazilian Amazon now either cut by roads or within 10 km of a road[2], continuous habitat is being perforated by edge effects. Globally, the average distance from any point in a tropical forest to the forest edge has shrunk, meaning animals that need interior conditions have less safe space.

-

Comparing Ratios Across Regions: The question requests comparing the “lowland to mountainous deforestation ratio” of one region to another. While exact quantified ratios are hard to pin down (due to varying definitions), we can qualitatively say: Southeast Asia likely has the highest imbalance – nearly all suitable lowlands deforested, with mountains holding much of what’s left (until recently). In Malaysia/Indonesia, you could say the area of lowland forest lost vastly exceeds area of mountain forest lost (since mountains weren’t many to start with). For example, in Sumatra, almost all lowland forest is gone, whereas some mountain parks remain – implying a very high lowland:upland deforestation ratio. Central Africa might have a lower imbalance – a lot of its lowland forest remains, and some mountain forests (like in Albertine Rift) are gone, so arguably more forest remains in lowlands than uplands (the opposite of Asia). South America’s Amazon vs Andes – the Amazon lowlands still largely forested (especially in west) while some Andean forests were cleared for farming at mid-elevations (though high Andes above certain altitude are not forest anyway). In the Amazon, the distinction is more between remote interior vs accessible edges rather than strictly low vs high elevation. However, in Atlantic Forest South America, lowland vs upland difference is huge: lowlands largely cleared, upland fragments remain. West Africa – almost everything cleared regardless of modest terrain differences, though a few upland refuges (like upland border of Nigeria-Cameroon) persisted slightly more. So West Africa’s ratio is also high (lowlands almost completely lost, a tiny bit in uplands remains). Central America – moderate ratio: significant lowland loss, but some lowlands remain (Mosquitia), and significant mountain loss, but some mountains remain (Sierra de las Minas in Guatemala, etc.). Possibly here swamps like Mosquitia were key, not just mountains.

To illustrate: In a region like Peninsular Malaysia, the lowland:upland deforestation ratio is very high – the coastal lowlands were 100% converted in many areas (rubber/palm cities), whereas uplands like Titiwangsa Mountains still have forests in Taman Negara, etc. On the other hand, in DRC in Central Africa, the majority of both lowland and upland forest is still there, but upland (like eastern highlands) did lose more due to farming. In Rwanda, an extreme case, almost all forest was in uplands originally and got cleared because people lived there, so lowland (which was savanna mostly) vs upland doesn’t apply exactly.

One recent scientific highlight: in mountainous regions globally, >65% have seen disproportionate forest loss at lower elevations[15], meaning lower slopes get deforested more heavily than upper slopes. This is essentially the ratio concept: it shows that mountain regions still have more forest higher up relative to what they originally had, compared to the foothills which were cleared.

Swamp vs non-swamp ratio: Many regions show that non-swamp forests have higher loss than swamp forests. For example, Indonesia’s peat swamp forests remained until late 1990s but then large portions were lost; still, some peat forests remain (e.g., in Aceh or parts of Borneo) whereas adjacent dry forests may be gone. In the Congo, swamp forests are almost entirely intact while adjacent terra firme forests have some logging and clearing near rivers. So one could say the proportion of original swamp forest remaining is higher than that of non-swamp forest in many countries. Mangroves too often have a higher remaining percentage compared to inland forests in the same region (though mangroves face unique threats like sea level rise now).

Conclusion

The “forest health” of the tropics is best where nature or terrain has made human exploitation difficult – high mountains, deep swamps, remote interiors – and worst where land was easily accessible and arable – flat lowlands, coastal plains, navigable river basins. Regions like Central Africa and New Guinea still benefit from this, having large contiguous forests in “unfavorable” lands (to farmers), whereas regions like West Africa or Southeast Asia had fewer natural barriers and thus suffered almost total lowland forest loss.

Moving forward, trends indicate that even those remaining refuges are under threat as technology (chainsaws, canals, road-building) and economic pressures grow. Conservation strategies increasingly focus on connecting fragmented forests (e.g., wildlife corridors over highways, reforestation of key linkages) and protecting the last intact landscapes (like the Amazon core, Congo peatlands, New Guinea) to preserve both biodiversity and ecosystem services. The differences between regions and forest categories underscore that we must tailor conservation to the context: protecting mountain cloud forests or swamp forests as last refuges in some places, while in others trying to restore lowland forests where possible. The percentage of forest remaining relative to original is a stark metric: globally roughly 66% of tropical forest cover remains (intact or degraded)[1], but in the healthiest regions (Amazon, Congo, New Guinea) it’s 70–85% remaining, whereas in the hardest-hit regions (West Africa, Southeast Asian islands) it’s on the order of 10–25% remaining. These numbers put into context how far along each region is on the path of deforestation. Without significant intervention, the risk is that regions with still-healthy forests could follow the same trajectory as those that have already been deforested – a fate we can foresee by comparing these regional differences today.

References

- Rainforest Foundation Norway. (2020). Only a third of the tropical rainforest remains intact – RFN report. Bioenergy International. https://bioenergyinternational.com/only-a-third-of-the-tropical-rainforest-remains-intact-rfn-report

- Mongabay. (2022, September). Road network spreads “arteries of destruction” across 41% of Brazilian Amazon. https://news.mongabay.com/2022/09/road-network-spreads-arteries-of-destruction-across-41-of-brazilian-amazon

- Earth.org. (2023). World Rainforest Day: The world’s great rainforests. https://earth.org/world-rainforest-day-worlds-great-rainforests

- Rainforest Foundation Norway. (2020). State of the Rainforest 2020 (PDF report). https://dv719tqmsuwvb.cloudfront.net/documents/Publikasjoner/Andre-rapporter/RF_StateOfTheRainforest_2020.pdf

- Olson, D. M., & Dinerstein, E. (2015). An overview of forest biomes and ecoregions of Central America. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280004414_An_overview_of_forest_biomes_and_ecoregions_of_Central_America

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Deforestation in Central America. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deforestation_in_Central_America

- Chazdon, R. L. (2008). Beyond deforestation: Restoring forests and ecosystem services on degraded lands. Ecological Economics, 68(3), 715–724. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959378008000186

- Earth Island Journal. (2019). The West Africa rainforest network: Local groups uniting for forest protection. https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/west_africa_rainforest_network/

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). (2023). Biodiversity and protected areas in West Africa. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/biodiversity-and-protected-areas-west-africa

- Chatham House. (2023, May). Deforestation in Africa: Drivers and policy options. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/05/deforestation-africa

- Curtis, P. G., Slay, C. M., Harris, N. L., Tyukavina, A., & Hansen, M. C. (2018). Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Environmental Research Letters, 13(1), 014009. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470160X20312085

- Butler, R. A. (2014, July). 30% of Borneo’s rainforests destroyed since 1973. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2014/07/30-of-borneos-rainforests-destroyed-since-1973

- Mongabay. (2021, June). Forest loss in mountains of Southeast Asia accelerates at shocking pace. https://news.mongabay.com/2021/06/forest-loss-in-mountains-of-southeast-asia-accelerates-at-shocking-pace

- Big Tree Seekers Group. (2023). Community discussion on world’s largest rainforest trees [Facebook post]. https://www.facebook.com/groups/BigTreeSeekers/posts/2226344931016075/

- University of Queensland. (2020). Ecosystem monitoring and large tree mapping datasets. UQ eSpace. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/

- Hello SmugMug

📸 Related Resources

- Visit our comprehensive travel guides for tropical regions such as Panama, Costa Rica, or Peru.

- Visit our ecolodges search page to find ecolodges in the tropics.

- Explore in-depth reviews of the remaining forest cover in Costa Rica or Panama.

About the Author: Michael Steinman is a web developer, wildlife photographer, and field naturalist specializing in reptiles and amphibians. Read more →

❓Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

How much tropical forest remains in the world today?

Roughly half of Earth’s original tropical forests remain, covering about 1.8 billion hectares worldwide.

-

What percentage of the world’s tropical forests are still considered intact wilderness?

Only about 35% of tropical forests remain truly intact and undisturbed by roads, logging, or development.

-

Which continent has the largest remaining tropical forests?

South America—particularly the Amazon Basin—contains more than half of the planet’s remaining tropical rainforest.

-

What defines a “healthy” or “intact” tropical forest?

A healthy forest is one that retains continuous canopy cover, native biodiversity, and natural ecosystem functions without major human disturbance.

-

How do primary and secondary tropical forests differ in biodiversity and structure?

Primary forests are old-growth ecosystems with complex canopy layers and high biodiversity, while secondary forests are younger, regrown areas with simpler structure and fewer species.

-

Where are the biggest continuous blocks of tropical forest located globally?

The largest wilderness blocks are in the Amazon Basin, the Congo Basin, and New Guinea.

-

Which regions of South America still have the most untouched rainforest?

Remote areas of Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and French Guiana retain vast stretches of old-growth forest.

-

Why are Africa’s tropical forests losing cover, and which areas remain most intact?

Deforestation from agriculture, fuelwood collection, and logging drives losses, though the Congo Basin still harbors immense intact forests.

-

How do lowland tropical forests differ from upland or montane rainforests?

Lowland forests are hotter, more diverse, and prone to deforestation, while upland forests are cooler, smaller, and more isolated.

-

What role do tropical forests play in regulating Earth’s climate and carbon cycle?

Tropical forests absorb billions of tons of CO₂ annually, stabilize rainfall, and influence global temperature regulation.

-

Which tropical countries are gaining forest cover instead of losing it?

Countries like Costa Rica, Panama, and Bhutan have achieved net forest recovery through strong conservation policies.

-

Can tropical forests fully recover after deforestation if left alone?

Natural regeneration can restore forest cover within 20–50 years, but original biodiversity may take centuries to recover. This is why losing primary forest is so consequential. Once it's gone, you'll never get it back...at least not within any person's lifetime.

-

How accurate are satellite measurements of tropical forest loss?

Modern systems such as Global Forest Watch use high-resolution satellite imagery to track deforestation with over 90% accuracy. That being said, different reports will have different confidence levels, and may define certain concepts differently. For example, the definition of "healthy" forest in this article was vague and subjective, and not likely to be universally agreed upon.

-

What global initiatives are protecting tropical wilderness areas?

Programs like the UN REDD+, Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, and 30x30 initiative aim to conserve and reconnect tropical forests

-

How do roads and infrastructure projects contribute to forest fragmentation?

Roads create edges and corridors that increase access for logging and settlement, often leading to rapid ecosystem fragmentation. Roads that are wide and busy enough to prevent most animals from crossing can be viewed as impenetrable barriers. So, if a section of land is bisected by a large road, we should view that section of land as two distinct sections, since animals need to live entirely within its confines. That means there is little to no gene flow in or out, and the animals within need to find all their food and resources within that area.

Large and migratory animals have a larger minimum amount of area to keep their populations stable. As an example, imagine a large migratory animal needs a minimum home range of 100 km2. An undivided wilderness area of 1000 km2 is more than enough to sustain this animal, but if roads break this area into sections, under 100 km2 each, then this wilderness can sustain none of this animal.

Thus, given two forests of equal size, the forest that is the least fragmented by roads or other barriers can sustain a greater number of animals, a greater diversity of animals, and a greater genetic diversity of each species.

-

Which tropical forests store the most carbon per hectare?