Costa Rica Forest Cover & Wilderness:

Conservation Success and Remaining Rainforests

The Extent and Health of Costa Rica’s Wild Forests Today | October 11, 2025

Last updated: October 12, 2025

This article is entirely independent and contains no sponsored content or affiliate links — it’s written to provide unbiased information for travelers. Title photo by Zdeněk Macháček.

🌿 Costa Rica’s Forests

Percentages are of total land area

Introduction

Costa Rica is world-renowned for its conservation efforts and lush ecosystems. But how much true wilderness remains, and how healthy are these wild lands today? This article explores Costa Rica’s current forest cover – distinguishing primary (old-growth) and secondary forests – and identifies the country’s largest contiguous blocks of wild, primary forest. We also put these figures in context, with relative percentages and comparisons to neighboring countries and other tropical regions.

Satellite Map

Click here to open a satellite map of Costa Rica in a new tab. While reading through this article, use this map to visualize the geography and forest cover. Dark green areas generally represent forest cover, while light green, and brown are often deforested areas, and grey to white are urban areas. Zooming in can reveal the types of forest (dense canopy), fragmented forests, or monoculture palm plantations.

Forest Cover: Extent and Recent Recovery

Costa Rica’s forests have undergone a remarkable turnaround in the past few decades. After deforestation reduced forest cover to as low as ~21% of the land in the 1980s, the country halted and reversed this trend. Today, roughly 57% of Costa Rica’s land is covered in forest, and about 25% of the nation’s territory is under protection[1]. This is a dramatic recovery by global standards – achieved through strong environmental policies, a ban on deforestation, ecotourism, and incentive programs like Payments for Environmental Services (PES). In fact, Costa Rica now gains more forest than it loses annually[2], a rare feat in the tropics.

Within this forest cover, the majority is natural forest (mostly tropical rainforest and cloud forest). According to satellite data from Global Forest Watch, in 2020 Costa Rica had about 2.63 million hectares (Mha) of natural forest, covering ~51% of its land area. (For reference, Costa Rica’s total land area is ~5.1 Mha.) On top of that, around 1% of the land (≈50,000–60,000 ha) consisted of tree plantations or other non-natural tree cover[3]. In sum, over half of Costa Rica is wooded, with the vast majority being native forest and a small fraction under plantation or agro-forestry.

It’s worth noting that Costa Rica’s forest cover includes both primary and secondary forests. Primary forest refers to old-growth, undisturbed forest – typically very biodiverse and structurally complex – whereas secondary forest is regrowth on previously cleared land (younger, with different species composition). As of 2001, an estimated 1.49 Mha of Costa Rica’s tree cover was primary forest, about 29% of the country’s land area. The remainder of the tree cover (~2.43 Mha in 2001) was secondary growth or plantation[3]. This indicates that by the turn of the century, roughly one-third of Costa Rica’s land still had old-growth forest, while two-thirds of the tree-covered land was regenerating forest or managed tree crops.

Crucially, Costa Rica has managed to retain most of that primary forest into the present. From 2002 through 2024, the country lost only about 31,100 hectares of humid primary forest to deforestation– roughly a 2% decline in primary forest area over two decades. This loss is comparatively low (it represents just 11% of Costa Rica’s total tree cover loss in that period[3], meaning most clearing affected secondary forests or plantations, not old-growth). In short, the vast majority of Costa Rica’s remaining primary forests are still intact, thanks to strong protections. Secondary forests have actually expanded in some areas due to natural regeneration and reforestation efforts, balancing out losses. This stability is unusual – data show that tree cover in Costa Rica (and Panama) was very stable year-to-year from 2015–2023, unlike many countries that see big fluctuations. Stable or increasing tree cover suggests that older forests are being conserved and regrowth is keeping pace with any removals, an encouraging sign for ecosystem health[4].

Primary vs. Secondary Forest Characteristics

Why does it matter how much forest is primary versus secondary? Primary rainforests typically harbor the highest biodiversity and fully intact ecological processes. These old-growth forests have towering canopy trees, rich multilayered structure, and specialist wildlife. In Costa Rica, primary forests are the strongholds for species like jaguars, Baird’s tapirs, harpy eagles, and scarlet macaws, which require large, undisturbed habitat. Secondary forests – those recovering after past logging or agriculture – are usually less biodiverse or missing certain old-growth specialist species. They tend to have thinner, smaller trees and a different species composition, at least in early stages of regrowth.

The good news is that Costa Rica’s secondary forests are maturing and expanding, helping to reconnect habitats. In many areas, what was pasture 30–40 years ago is now dense jungle again. These secondary stands, once they reach a certain age, can provide good habitat for many animals and can eventually attain old-growth characteristics. For example, over 90% of Braulio Carrillo National Park’s 47,000+ hectares is considered primary rainforest, even though some edges were once logged[5] – essentially the forest has regrown to a primary-like state over time. Secondary forests also provide vital buffers and corridors between the primary forest cores.

In Costa Rica today, roughly half of the remaining forest cover is primary (old-growth) and half is secondary/regrown (based on the 1.5 Mha primary vs ~1.1 Mha other natural forest). Because deforestation has been curbed, much of the secondary forest is progressing toward a more mature state. This bodes well for the country’s ecological resilience – a larger expanse of continuous, healthy forest cover means better support for wildlife, carbon storage, and ecosystem services like water regulation.

“Non-Natural” Tree Cover: Plantations and Agriculture

Not all tree cover is natural forest. Costa Rica does have significant areas of tree plantations and agro-forestry – notably oil palm plantations in the lowlands, and some timber plantations (teak, melina, etc.) in various regions. These are essentially agricultural lands and do not constitute “wilderness,” though they appear as tree cover in satellite images. It’s important to account for them when assessing wild forest extent.

Oil palm (African oil palm, Elaeis guineensis) has become a major crop in parts of Costa Rica’s Pacific and Caribbean lowlands. As of 2020, approximately 265,000 hectares of land in Costa Rica were dedicated to oil palm cultivation[6]. (This is about 5% of the country’s land area – a substantial portion, though much smaller than in some Southeast Asian countries where oil palm dominates the landscape.) Oil palm plantations are concentrated in the southwest (the Osa Peninsula/Golfo Dulce region and adjacent valleys) and the central Pacific coast, as well as some areas in the Caribbean Talamanca region. For instance, in Puntarenas Province, oil palm accounts for the largest plantation area (around 63.5 thousand ha), making up about 70% of that province’s cultivated tree plantations[3]. Nationally, the expansion of palm oil has been significant – between 2005 and 2017 the area under oil palm grew by 24%, from about 207,000 ha to 257,120 ha[7]. While these plantations contribute to Costa Rica’s economy, they replaced some natural ecosystems and do not support the same biodiversity. Monoculture groves of palm have a simplified structure and little understory, providing poor habitat for most wildlife beyond some generalist species.

Beyond palm, Costa Rica has tree plantations for timber (such as teak and pine in the drier northwest, and eucalyptus in some areas). These are smaller in extent – on the order of tens of thousands of hectares. Global Forest Watch data suggested only about 1% of Costa Rica’s land (≈52,000 ha) was under non-natural tree cover as of 2020[3], which likely reflects mainly timber plantations. (The oil palm figure is higher; the discrepancy is because oil palm often isn’t counted as “forest cover” in some datasets due to its agricultural classification, even though it is tree cover from a satellite perspective.) In any case, when considering “wilderness,” we exclude these plantation areas – they are effectively agricultural land, typically in uniform rows, often with intensive management. They lack the ecological value of natural forests.

For context, Costa Rica’s situation is far better than many tropical countries in this regard. In Southeast Asia, for example, oil palm plantations cover enormous areas – globally over 27 Mha are planted with oil palm[8], much of it replacing rainforests in Indonesia and Malaysia. A single plantation in Sumatra can span hundreds of thousands of hectares. By contrast, Costa Rica’s ~0.26 Mha of palm is relatively small and fragmented. Moreover, Costa Rica’s plantations have largely been established on former pasture or already-cleared land, not by cutting pristine rainforest (especially in recent decades, given the deforestation ban). This is one reason the EU recently classified Costa Rica as a “low-risk” country for deforestation-linked commodities[2]. Still, the proliferation of plantations does reduce the extent of natural wilderness and can fragment habitats if not planned carefully.

Major Contiguous Wild Forest Areas in Costa Rica

One way to gauge the “wild health” of Costa Rica is to look at its largest contiguous blocks of primary forest. These are the big wilderness strongholds – large enough to sustain complete ecosystems, including wide-ranging animals like jaguars or tapirs, and to preserve ecological processes. While small forest patches are still valuable, they cannot support the full range of biodiversity (for instance, a tiny forest fragment likely won’t hold a breeding jaguar population or intact predator-prey dynamics). Costa Rica’s conservation network includes several large forest complexes, mostly centered on national parks and indigenous reserves. Below, we highlight six of the most significant contiguous wilderness areas in Costa Rica, discussing their extent, location, and ecological “health”:

1. Talamanca Mountain Range (La Amistad International Park and Reserves)

Location: Southeastern Costa Rica, along the border with Panama, spanning parts of Limón and Puntarenas provinces.

Extent: This is Costa Rica’s largest continuous forest area, part of a transboundary World Heritage Site. The combined protected complex – La Amistad International Park and adjacent Talamanca reserves – covers about 570,000 ha in total, of which roughly 349,000 ha lie on the Costa Rica side[9]. It stretches from lowland tropical rainforest up to montane cloud forests and even alpine páramo at over 3,500 m elevation. Large contiguous forest tracts extend from the Panama border (and well into Panama), north to the Caribbean lowlands near Siquirres. Contiguous forests cover the majority of the Atlantic/Caribbean side of the continental divide from Panama in the south to Highway 32 in the north, with some continuously forested corridors all the way to the Caribbean coast.

While most of the Pacific side has been deforested or is composed of small fragmented forest patches, continuous forested corridors, following ridge lines and river edges extend from the Talamancan mountains to the Pacific lowlands. From roughly Los Quetzales NP in the mountains, south west to Manuel Antonio National Park, these continuous corridors can almost reach the Pacific coast.

Health and Significance: The Talamanca Range contains “one of the major remaining blocks of natural forest in Central America”. Because of its elevation span and connectivity, it harbors extraordinary biodiversity and endemism – from quetzals and tapirs in cloud forests to rare high-altitude oaks and paramo plants[9]. Much of this forest is primary and essentially intact, owing to rugged terrain and decades of binational protection. Indigenous territories overlap parts of this wilderness, notably the Bribri, Cabécar, and Ngäbe communities, whose stewardship has also helped conserve the forest. In terms of wildlife, Talamanca is a crucial refuge for large mammals – it has stable populations of Baird’s tapir and a significant portion of Costa Rica’s jaguars, as well as pumas, peccaries, and birds ranging from eagles to hummingbirds. The “health” of this block is generally high: its core is roadless and without major fragmentation. However, some lower elevation edges (e.g. in the Valle de El General or Caribbean foothills) face pressures from agriculture and settlers, which makes continued corridor protection important. Overall, Talamanca’s vast, contiguous nature makes it a lifeboat for species needing big territories. It is the kind of landscape where one could wander for days in unbroken wilderness – increasingly rare in Central America.

2. Osa Peninsula (Corcovado – Golfo Dulce Forest Complex)

Location: Southwest Costa Rica, in Puntarenas province. The Osa Peninsula juts into the Pacific Ocean, separated from the mainland by the Golfo Dulce.

Extent: The Osa region’s forests include Corcovado National Park (424 km² of core protected forest), plus the surrounding Golfo Dulce Forest Reserve, Piedras Blancas National Park, and Térraba-Sierpe wetlands. Much of the peninsula’s 80,000–100,000 ha land area remains forested. Corcovado NP alone protects about a third of the peninsula[10], and additional contiguous forest extends beyond the park boundaries. This area forms the largest continuous lowland rainforest on the Pacific coast of Central America[11].

Health and Significance: Osa’s forests are often described as “the most exuberant lowland tropical rainforests remaining in Pacific Mesoamerica”[12]. They are remarkably biodiverse – the peninsula contains 2.5% of the entire planet’s biodiversity in a tiny area[11]. Corcovado NP is famous for having the largest primary forest on the American Pacific coastline, including extensive stands of towering giant trees. Wildlife is abundant: all four Costa Rican monkey species thrive here, as do large predators and prey – jaguars, pumas, ocelots, Baird’s tapirs, collared peccaries, and even a remnant harpy eagle population[10]. The marine and coastal interfaces (mangroves, lagoons, beaches) add to the ecological richness (e.g. nesting sea turtles, crocodiles). In terms of integrity, the Osa forest block is in very good condition internally – Corcovado’s core is pristine primary forest, and logging was halted in the 1970s. The main concern is isolation: the Osa’s rainforest is geographically separated from other mainland forests by farms and settlements on the narrow land bridge to the rest of Costa Rica[11]. This limits genetic exchange for some species (though efforts are underway to maintain a biological corridor northward, the “Path of the Tapir”). Despite that, Osa is large enough to support viable populations on its own for many species, and it remains a top conservation priority. Scientists often point out that Osa is one of the last places where tropical nature in Central America remains almost as it was centuries ago – a true wild rainforest experience.

3. Guanacaste Conservation Area (Northwest Dry Forests)

Location: Northwestern Costa Rica (Guanacaste Province), along the Pacific coast up to the Nicaragua border.

Extent: The Guanacaste Conservation Area (ACG) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site encompassing a contiguous block of about 147,000 ha of land and marine area, including 104,000 ha of terrestrial habitats. It spans from the shoreline and coastal dry forests (Santa Rosa National Park) through the lowland deciduous forests and into the volcanic mountain range of Guanacaste (including Rincon de la Vieja and Guanacaste National Parks). This continuum stretches roughly 100 km from sea level on the Pacific to high-elevation forests approaching the Caribbean slope.[13]

Health and Significance: This area protects the largest remaining tract of tropical dry forest in Central America (from Mexico to Panama). Tropical dry forest is a rare and highly threatened ecosystem; Guanacaste’s examples are considered of global importance. The conservation area is a mosaic of habitats – not just dry forest but also patches of evergreen forest in riparian areas, montane cloud forest at higher altitudes, oak woodlands, savannas, and wetlands. Ecologically, Guanacaste was once heavily deforested for cattle ranching; by the 1980s much was degraded pasture. The “health” of this wilderness today is a testament to restoration: large areas have been rewilded and allowed to regenerate, so secondary forests now cover former pastures and are maturing steadily. In parallel, key fauna have made a comeback. ACG now hosts species like the endangered Central American tapir, as well as jaguars, pumas, white-tailed deer, and an incredible diversity of bats, birds, and insects[13]. Research and active restoration (including tree planting and fire control) have been part of the management. While the dry forest here is more patchy and deciduous (even leafless in dry season) compared to a rainforest, it represents a fully functioning wild landscape, especially in the wet season when it bursts with life. Connectivity within the ACG is good (all the parks connect), but the complex is somewhat isolated from other forest areas except at its highest elevations (where it nearly meets forests of the central cordillera). Overall, Guanacaste’s protected block is large enough to sustain its unique assemblage of wildlife and is considered a success story of forest recovery. It exemplifies how even extensively cleared land can be rewilded to a semblance of its original wilderness.

4. Northern Caribbean Lowland Forests (Tortuguero–Barra del Colorado–Maquenque)

Location: Northeastern Costa Rica (Limón and northern Alajuela provinces), along the Caribbean coast and the San Juan River (border with Nicaragua).

Extent: This is a somewhat linear but extensive swath of forested wetlands and lowland rainforest. It includes Tortuguero National Park (a 26,000+ ha terrestrial park, plus 50,000 ha of marine area)[14], the adjacent Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge (about 81,177 ha of lagoons, wetlands, and flooded forest[15]), and the inland Maquenque Wildlife Refuge (~60,000 ha of forest and wetlands in the San Carlos region). Together these protected areas and surrounding biological corridors create a mosaic of tropical wet forest stretching from the coast inland along the Nicaragua border. Notably, this complex connects to the Indio Maíz Reserve just across the border in Nicaragua – a huge wilderness of ~300,000+ ha of forest[16][17]. The Costa Rican side of this binational expanse might total on the order of 150,000 ha of contiguous habitat when including Tortuguero, Barra del Colorado, Maquenque and intervening forest patches.

Health and Significance: The northern Caribbean forests are characterized by flat terrain, winding rivers, and swampy areas that historically limited human settlement – hence large tracts remain wild. These forests are extremely rich in water resources (rivers, canals, wetlands) and support creatures adapted to both land and water: endangered species like the West Indian manatee inhabit the waterways, while jaguars and ocelots prowl the jungle (Tortuguero has one of the highest densities of jaguar sightings, partly because jaguars there prey on nesting sea turtles along the beach). The area is also famed for migratory birds and as a nesting ground for green sea turtles on the Caribbean beaches. In terms of forest cover, much of it is primary or mature secondary rainforest – for example, Barra del Colorado protects vast tracts of lowland “flooded” rainforest and palm swamps that are largely intact[15]. The contiguity with Nicaragua’s Indio Maíz Reserve is crucial: it forms a binational corridor allowing wildlife to roam a huge area (collectively one of Central America’s biggest remaining wilderness blocks). On the Costa Rica side, habitat continuity is pretty good, though the San Juan River marks the border and some stretches outside parks have farmland (mostly small-scale). The creation of Maquenque Refuge in 2005 was intended to secure a corridor for great green macaws and other species between northern CR and Indio Maíz. There are still some gaps to fully reforest, but generally this region’s forests are functioning and connected. One can travel by boat from Tortuguero northwards and be surrounded by forest and wetlands for dozens of kilometers. Human impact is low in the core (no roads penetrate Tortuguero or Barra del Colorado; access is only by boat or plane). The “health” of this area is relatively high, though illegal fishing, hunting, and some timber extraction occur at low levels, and on the Nicaragua side deforestation has been a concern. Overall, this northern Caribbean strip is a vital stronghold for lowland biodiversity, complementing the Pacific’s Osa Peninsula on the opposite coast.

5. Central Cordillera Rainforests (Braulio Carrillo and Central Volcanic Range)

Location: Central Costa Rica, north and east of San José, spanning parts of Heredia, Alajuela, and Cartago provinces – essentially the Atlantic slope of the central volcanic range.

Extent: The centerpiece is Braulio Carrillo National Park, which covers about 47,000–50,000 ha of dense rainforest on the steep slopes of the Cordillera Central[5][18]. Braulio Carrillo connects montane cloud forests near Barva and Irazú volcanoes (over 2,900 m elevation) down to lowland rainforest at only ~30 m above sea level – an incredible gradient all contained in one protected area. Adjoining Braulio are a number of other reserves and forest fragments: to the west, it nearly connects with Poás Volcano NP and private reserves (though not contiguously); to the east and north, Braulio’s forests transition to the Sarapiquí plains where the La Selva Biological Station (1,600 ha of old-growth) and other private reserves act as stepping stones toward the aforementioned Maquenque/Barra del Colorado area. This whole central region is more fragmented than the previously mentioned blocks, but Braulio Carrillo NP itself is a solid, contiguous wilderness. There are proposals for biological corridors (e.g. San Juan–La Selva Corridor) to better link Braulio with northern forests – if realized, it would create a continuous protected swath of 348,000 ha from central Costa Rica to the Nicaragua border[19]. Currently, Braulio is separated by some gaps, but not by great distances.

Health and Significance: Braulio Carrillo NP is often called one of the wildest jungles in Costa Rica, remarkably close to the capital. Over 90% of its forest is primary rainforest[5], meaning ancient trees and undisturbed habitat dominate. The park is so dense and inhospitable that large portions have never had trails. It protects seven distinct life zones from high-altitude cloud forest to lowland wet forest[5], harboring thousands of plant species and over 500 bird species. Ecologically, this area serves as a critical corridor between highland and lowland ecosystems – animals like tapirs and jaguars use these mountains to move between the coasts or to reach various elevations seasonally. The main human impact is a highway (Route 32) that unfortunately cuts through Braulio Carrillo NP for accessibility to the Caribbean port; this road has fragmented the habitat to a degree and causes wildlife mortality by vehicle strikes. However, aside from the corridor along the road, the interior of the park remains very healthy and intact. Park guards and policies generally keep logging and farming out. The surrounding private reserves and indigenous lands (like Bajo Chirripó Reserve on the Caribbean slope) add buffer. In summary, while this central forest block is not as continuously expansive as Talamanca or Osa, it represents a large, biodiverse wild area in its own right. Efforts to connect it with the northern lowland forests would further enhance its ecological health by allowing gene flow and species movement across a greater landscape.

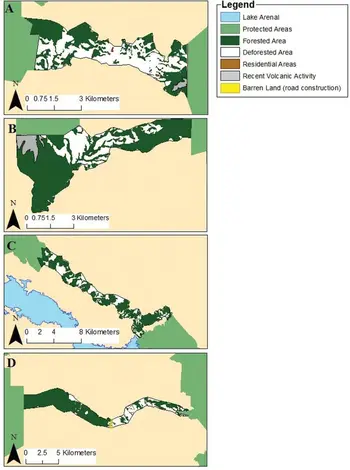

6. Monteverde–Arenal (Tilarán / Northern Volcanic Corridor

Location: The forested region between Monteverde (in the Cordillera de Tilarán) and Volcán Arenal constitutes a mid-elevation cloud-forest / montane-rainforest corridor. Monteverde’s core reserve lies along the Tilarán ridge (spanning Puntarenas and Alajuela provinces) with about 10,500 ha of forested cloud forest in the main reserve.[21] The Monteverde Biological Preserve is also embedded within a broader Bellbird Wildlife Corridor, which is part of the Arenal-Monteverde Protected Zone plan managed by SINAC.[22] Ecologically, this corridor covers steep ridges, cloud-forest slopes, and transitional zones toward lower-elevation rainforest near Arenal. Monteverde’s cloud forests are known for very high biodiversity and many endemic species, making this stretch biologically important.

Potential Connectivity & Corridor Opportunities: From the Monteverde–Arenal patch, the nearest large contiguous forest block is Volcán Tenorio (to the northwest). Between Monteverde/Arenal and Tenorio, there is an agricultural gap but it is not insurmountable: the mosaic of forest patches and low-intensity land use suggests that wildlife (especially larger mammals) could traverse these lands under the right conditions or with strengthened corridors. In conservation planning maps, this corridor is explicitly proposed (Arenal ↔ Tenorio corridor) by SINAC as a sub-corridor.[23]

From Tenorio, there is a relatively short agricultural gap separating the forest block around Volcán Miravalles, which itself is somewhat contiguous. Some mapping proposals call for a Miravalles–Tenorio corridor (label B in corridor maps) to bridge these blocks.[23]Once those links are in place, the gap between Miravalles and the northwest Guanacaste forest complex is only on the order of a few miles (≈3 miles in some estimates). That gap could potentially be reforested or overlaid with narrow secondary forest corridors to connect Miravalles with the Guanacaste block (your previously discussed major patch).[24]

In effect, with careful corridor design and reforestation work, it is conceivable that all six major forest complexes in Costa Rica—from the NW Guanacaste block through Miravalles, Tenorio, Monteverde–Arenal, then crossing toward central Cordillera, northern Caribbean, and finally linking into Talamanca / Osa toward Panama—could be stitched together into a continuous or semi-continuous web of forest connectivity. Such a corridor network would enable gene flow, species dispersal, climate-migration routes, and greater resilience to fragmentation.

These six regions – Talamanca, Osa, Guanacaste, the Northern Caribbean, Monteverde, and the Central Cordillera – form the core of Costa Rica’s remaining wilderness. Each has different forest types (montane vs. lowland, rainforests vs. dry forests), giving Costa Rica a rich natural heritage across a small country. Impressively, each of these blocks is large enough to support top predators and complete ecosystems, which is why sightings of jaguars, tapirs, and other sensitive fauna are regularly recorded in all of them. Contiguity matters: a scattered collection of tiny forest patches cannot maintain viable populations of such animals. Costa Rica recognized this and invested in large protected areas and biological corridors to stitch patches together. The result is that, unlike many tropical countries, Costa Rica still has multiple large-scale wild landscapes rather than only isolated pockets.

Comparative Context

To appreciate the extent of Costa Rica’s wild lands, it helps to compare with regional neighbors and other tropical regions:

- Central America: Costa Rica (with ~57% forest cover) is among the most forested countries in the region by percentage. Panama, by comparison, has roughly 60% forest cover and also boasts large wild areas (e.g. the Darien region, with contiguous forest >500,000 ha). However, Panama’s deforestation rates in some areas have been higher, and its protected percentage (~20% of land) is slightly lower than Costa Rica’s[2]. Nicaragua – larger in area but less developed – still has some wilderness in the north (the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, ~2 million ha, is Central America’s single largest forest)[25] and in the south (Indio Maíz ~300k ha). Yet Nicaragua’s overall forest cover has plummeted to perhaps 25–30%, meaning outside those reserves much has been cleared. To make matters worse, most of Nicaragua from north to south has been mostly clear cut for agriculture, with only small fragmented patches in between. Costa Rica, despite its smaller size, managed to reconnect many of its forest fragments, whereas Nicaragua faces rapid fragmentation of its big reserves (e.g. Bosawás has suffered serious cattle-driven deforestation in its buffer zones[26][27]). In Guatemala and Honduras, forest cover is around 30–40% and declining, with remaining wilderness concentrated in specific areas (Maya Biosphere in Guatemala, La Mosquitia in Honduras) but extensive losses elsewhere. Against this backdrop, Costa Rica’s achievement – stable forest cover, low primary forest loss, and low risk of deforestation as recognized by the EU– truly stands out. It is the only Central American country classified as “low risk” for deforestation-linked commodities under the EU’s new regulation[2]. Southeast Asia: This region provides a cautionary counterpoint. Countries like Indonesia and Malaysia had forest cover percentages similar to or higher than Costa Rica historically, but plantation agriculture (oil palm, rubber, pulpwood) and logging have severely fragmented their forests. For example, Indonesia lost ~1.18 Mha of forest in 2023 alone[28], much of it primary. In Borneo and Sumatra, large contiguous forests still exist (some on the scale of 1–2 Mha in national parks or interior highlands), but these are increasingly islands amid plantations. By contrast, Costa Rica has largely avoided industrial plantation expansion at the expense of primary forests – the ~0.26 Mha of oil palm in Costa Rica is minuscule next to Indonesia’s ~16 Mha of oil palm and even Malaysia’s ~5 Mha, and in Costa Rica it was often planted on already-cleared land. The result is that a much higher fraction of Costa Rica’s tree cover is natural forest as opposed to monoculture. Moreover, about 25% of Costa Rica’s land is strictly protected, whereas countries in Southeast Asia protect a smaller fraction of their forests. For instance, Malaysia has set aside some reserves (especially in Borneo), but large areas of “protected” forest in SE Asia have still been logged or degraded. In Costa Rica, even protected areas have issues (poaching, some illegal logging), but they have generally maintained forest cover – a recent analysis showed that globally about 39% of tropical primary forests are in protected areas[29], and Costa Rica is certainly contributing to that statistic with its robust park system.

- South America: Of course, Costa Rica is tiny next to the Amazon Basin countries. Brazil, Peru, and Colombia each have tens of millions of hectares of rainforest, including vast untouched cores (but also high absolute deforestation). The Amazon’s intact areas dwarf anything in Mesoamerica. However, looking at relative protection and management, Costa Rica is often held up as a model – it protected a larger share of its forests and reversed deforestation trends earlier. Many Amazonian countries still struggle with frontier expansion, whereas Costa Rica’s forest frontier is largely stabilized.

- Global perspective: In 2023, the tropics lost about 3.7 Mha of primary rainforest worldwide (mostly in the Amazon, Congo, and Southeast Asia)[28]. That single-year global loss is more than the total remaining primary forest area in Costa Rica. This underscores that Costa Rica alone is small in absolute terms, but its importance is outsized in conservation circles: it shows how a country can maintain and even restore forests. The country’s remaining wilderness, while not vast like the Amazon or Congo, is disproportionately valuable. Each hectare in Costa Rica is intensely biodiverse – for example, the Osa Peninsula has more tree species in 100 km² than some temperate countries have in their entirety. The connectivity Costa Rica preserved between its wild areas (through biological corridors linking many of the five blocks described) is also a model that many larger nations are trying to emulate.

In summary, Costa Rica’s wilderness is in a relatively healthy state, especially when viewed relatively (percent cover, protection level, stability) against many peers. Over half the country is under forest, and roughly half of that is old-growth primary forest – a high ratio for any nation. The largest forest complexes (Talamanca, Osa, etc.) each span tens to hundreds of thousands of hectares, which is sufficient to keep ecological processes intact inside them. These wild lands are not just isolated parks; they are increasingly connected by reforested corridors, allowing wildlife to move between them. As a result, species that elsewhere are in decline – jaguars, tapirs, monkeys, big cats – have stable or recovering populations in Costa Rica’s wild areas.

Of course, challenges remain. Habitat fragmentation at the edges, agricultural encroachment, climate change impacts, and development pressures all require continual management. For instance, maintaining corridors so that Osa’s isolated population of Baird’s tapirs can mix with those in Talamanca is an ongoing effort. Invasive species and diseases (like fungal blights in cloud forests) are concerns. And as a small country, Costa Rica’s wilderness will always be relatively limited in extent – it must rely on transboundary conservation (with Panama and Nicaragua) to secure some wide-ranging species. Nonetheless, the overall picture is one of a thriving natural landscape for a country of its size.

Conclusion

Costa Rica offers a heartening case study of wild land conservation. Roughly 57% of the nation is forested, a figure that has been stable or rising in recent years[1][2]. About one-quarter of the country is strictly protected, and large swaths of primary rainforest remain intact in several key regions (each home to flagship species and full ecosystems). Primary forests cover around 1.5 million hectares (nearly 30% of the country), and only a very small fraction of these have been lost in the last two decades[3]. Secondary forests and reforestation have further expanded tree cover, knitting the landscape together. Meanwhile, non-natural tree cover (like plantations) constitutes a relatively small portion of land (~5–6%), and even those are often outside the critical biodiversity areas

In practical terms, a nature enthusiast in Costa Rica can experience true wilderness in multiple corners of the country – be it trekking through the misty, pathless cloud forests of Talamanca, listening to howler monkeys in the regenerated dry forests of Guanacaste, or watching a jaguar’s paw prints along Osa’s deserted beaches. The extent and health of Costa Rica’s wild lands are exceptional given its human population and agricultural history. Many factors contributed to this success, from forward-thinking government policies to grassroots restoration projects and indigenous stewardship.

When comparing to other tropical regions, Costa Rica’s forests may be small in absolute area, but they are a larger proportion of the country and better preserved than most. The country demonstrates that deforestation is not an inevitable destiny – forests can be saved and even brought back, yielding benefits for biodiversity, climate, and people. The remaining wilderness in Costa Rica is not only a treasure trove of species found few other places, but also a source of national pride and a cornerstone of sustainable ecotourism and rural livelihoods.

In conclusion, Costa Rica has approximately half of its land under forest cover, about half of that forest is primary old-growth, and the majority of these forests form contiguous, resilient wild areas rather than tiny fragments[3]. The five largest forest complexes – in the Talamanca highlands, Osa Peninsula, Guanacaste dry forests, Northern Caribbean wetlands, and central cordilleras – each represent critical reservoirs of wilderness that can support complete ecosystems, from top predators to endemic plants. These wild lands are among the healthiest in Latin America, and they offer hope that with committed conservation, a country can safeguard its natural heritage. Costa Rica’s experience suggests that even as the world faces a biodiversity crisis, it is possible to maintain and even enhance the extent of wilderness with the right mix of policy, protection, and restoration. For nature enthusiasts and researchers alike, Costa Rica’s forests remain a living laboratory of how human society can coexist with thriving wild ecosystems.

References

- Vincenzi, D. (2024, July 15). Conservation pays and everyone’s benefitting from it [Commentary]. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2024/07/conservation-pays-and-everyones-benefitting-from-it-commentary

- Tico Times. (2025, May 26). Costa Rica celebrates EU’s low-risk deforestation classification. The Tico Times. https://ticotimes.net/2025/05/26/costa-rica-celebrates-eus-low-risk-deforestation-classification

- Global Forest Watch. (2024). Costa Rica dashboard. World Resources Institute. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/CRI/

- World Resources Institute. (2024). Tree cover is declining in Latin America—but new data show where it’s increasing. https://www.wri.org/insights/tree-cover-declining-latin-america-new-data-shows-where-increasing

- Aqua-Firma. (n.d.). Braulio Carrillo National Park—Costa Rica travel guide. https://www.aqua-firma.com/[…]

- Grow Jungles. (2023). Costa Rica’s African palm oil dilemma: Unraveling the ecological catastrophe. https://growjungles.com/[…]

- Bravo, M. (2022). Estudio sobre la expansión del cultivo de palma africana en Costa Rica [PDF]. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. https://repositorio.uasb.edu.ec/[…]

- Rainforest Rescue. (n.d.). Palm oil: A major cause of deforestation. https://www.rainforest-rescue.org/topics/palm-oil

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). La Amistad International Park. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/205/

- Wikipedia. (2024). Corcovado National Park. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corcovado_National_Park

- Tamandua Expeditions. (2023, December). Osa Peninsula: All you have to know about it. https://www.tamanduacr.com/[…]

- Key Biodiversity Areas. (n.d.). Osa Peninsula and Golfo Dulce KBA factsheet (Site 20414). https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/site/factsheet/20414

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). Guanacaste Conservation Area. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/928/

- Wildlife Conservation Society. (n.d.). Indio Maíz–Tortuguero: The Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica. https://programs.wcs.org/[…]

- Visit Costa Rica. (n.d.). Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge. https://www.visitcostarica.com/blog/[…]

- Mongabay. (2021, December). Agricultural frontier advances in Nicaraguan biosphere reserve. https://news.mongabay.com/[…]

- Mapa Nicaragua. (n.d.). Indio Maíz Biological Reserve. https://www.mapanicaragua.com/en/[…]

- SINAC. (n.d.). Braulio Carrillo National Park official page. https://www.sinac.go.cr/[…]

- Laurance, W. F., et al. (2005). Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 211(1-2), 1-20. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0016328705001394

- Go Visit Costa Rica. (n.d.). Arenal Volcano area overview. https://www.govisitcostarica.com/[…]

- Wikipedia. (2024). Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monteverde_Cloud_Forest_Reserve

- Cloud Forest Monteverde. (n.d.). Conservation of nature. https://cloudforestmonteverde.com/conservation-of-nature/

- ResearchGate. (2019). Proposed biological sub-corridors within protected lands and Costa Rican government plans. https://www.researchgate.net/[…]

- Pensoft Publishers. (2018). Nature Conservation Journal: Corridor planning in Costa Rica. https://natureconservation.pensoft.net/article/27430/

- Wikipedia. (2024). Bosawás Biosphere Reserve. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bosaw%C3%A1s_Biosphere_Reserve

- Mongabay. (2017, March). Cattle ranching devours Nicaragua’s Bosawás Biosphere Reserve. https://news.mongabay.com/[…]

- South World. (2018). Nicaragua: Bosawás Biosphere Reserve under threat. https://www.southworld.net/nicaragua-bosawas-biosphere-reserve-under-threat

- Forest Declaration Assessment. (2024). 2024 Forest Declaration Assessment report. https://forestdeclaration.org/[…]

- Global Forest Review / World Resources Institute. (2024). Protected forests: Designation indicators. https://gfr.wri.org/forest-designation-indicators/protected-forests

📸 Related Resources

- Visit our comprehensive travel guide for Costa Rica.

- Visit our ecolodges search page to find ecolodges in Costa Rica.

About the Author: Michael Steinman is a web developer, wildlife photographer, and field naturalist specializing in reptiles and amphibians. Read more →

❓Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

How much of Costa Rica is still covered by forest?

About 57% of Costa Rica’s land area remains under forest cover, making it one of the most forested nations in the tropics.

-

What percentage of Costa Rica’s remaining forest is primary old-growth?

Roughly half of Costa Rica’s forest—around 1.5 million hectares—is primary old-growth rainforest that has never been cleared.

-

Which are the largest contiguous wilderness areas in Costa Rica?

The six main forest blocks are Talamanca, Osa Peninsula, Guanacaste, Northern Caribbean, Central Volcanic, and Monteverde–Arenal.

-

What role do secondary forests play in Costa Rica’s ecosystems?

Secondary forests are regrowing on former farmland, expanding habitat connectivity and gradually regaining old-growth structure.

-

Has Costa Rica successfully reversed deforestation?

Yes. Since the 1980s Costa Rica has gone from ~21% to ~57% forest cover, thanks to strong environmental policies and reforestation incentives.

-

Can Costa Rica eventually connect all six major forest blocks through wildlife corridors?

Ecologists believe it’s possible; strategic reforestation could create continuous corridors from Nicaragua to Panama.

-

How does Costa Rica’s forest recovery compare to Panama or Nicaragua today?

Costa Rica’s recovery is the strongest in Central America. It has stabilized at about 57 % forest cover with very low annual deforestation and roughly 25 % of its land protected. By contrast, Panama retains about 60 % forest cover, but its lowland areas—especially in Darién and Bocas del Toro—face higher deforestation pressure, and only about 20 % of its land is formally protected. Nicaragua, though much larger, has suffered severe losses: forest cover has fallen to around 25–30 %, and even vast reserves like Bosawás and Indio Maíz are rapidly fragmenting from cattle expansion. Overall, Costa Rica remains the regional model for reversing deforestation and maintaining stable, connected wilderness.

-

What species benefit most from large continuous forest areas?

Wide-ranging animals such as jaguars, tapirs, and great green macaws depend on intact wilderness for viable populations.

-

Are Costa Rica’s cloud forests at risk from climate change?

Yes — Costa Rica’s famed cloud forests, such as those in Monteverde and the Talamanca range, are among the ecosystems most vulnerable to warming. Rising temperatures are pushing the cloud base to higher elevations, reducing the persistent mist that defines these forests. This can dry mosses, epiphytes, and bromeliads that depend on constant moisture, and alter conditions for amphibians and birds like the resplendent quetzal. Some species may migrate upslope, but mountaintop habitats are limited. Ongoing monitoring by Costa Rican and international researchers shows that maintaining broad elevational corridors — linking lowland and highland forests — will be essential for long-term adaptation.

-

How can visitors or ecotourists support reforestation and corridor projects?

Travelers can support local conservation NGOs, stay at ecolodges practicing forest restoration, and choose low-impact travel options. Visit our ecolodges search page to find ecolodges in Costa Rica.