Panama Travel Guide

Comprehensive Travel Guide for Herpers, Birders, and Ecotourists

Exploring Panama: A Comprehensive Guide for Wildlife Enthusiasts, Herpers, and Ecotourists

Introduction to Panama

Photo Credit: Addicted04, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Panama is a land of extraordinary ecological and geographic diversity, where the lush rainforests of the Darién meet the pristine beaches of the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. This narrow isthmus, connecting North and South America, is more than just a bridge between continents—it is a hotspot of biodiversity, home to an incredible array of wildlife found nowhere else in the world. From the misty cloud forests of the Chiriquí Highlands to the vibrant coral reefs of Bocas del Toro, Panama offers ecotourists an unparalleled opportunity to explore a variety of habitats in a compact and easily navigable country.

For herpers, birders, and wildlife photographers, Panama is a dream destination, boasting an impressive range of species across its national parks and protected areas. With over 250 species of amphibians and reptiles, including the strikingly beautiful eyelash viper and the elusive Panama golden frog, the country is a paradise for herpetologists. Birders will find themselves in one of the richest avian regions in the world, with nearly 1,000 recorded bird species, including iconic residents like the resplendent quetzal and harpy eagle. Whether trekking through the dense lowland jungles of Soberanía National Park or scanning mangrove-lined waterways for rare species, Panama rewards visitors with unforgettable wildlife encounters at every turn.

This guide is designed to help ecotourists make the most of their journey through Panama by providing detailed insights into the country’s best destinations for wildlife viewing, photography, and exploration. From practical advice on travel logistics and lodging to in-depth recommendations on where and how to find the country’s most sought-after species, this resource will serve as a comprehensive companion for nature enthusiasts. Whether you’re venturing into the depths of Coiba National Park, hiking the legendary Pipeline Road, or searching for nocturnal creatures in the forests of Gamboa, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and inspiration needed to experience Panama’s wild side to the fullest.

Understanding Panama’s Geography, Biodiversity, and Ecotourism Opportunities

Exploring Panama’s Diverse Geographic Regions

Panama’s geography is defined by its role as a land bridge between North and South America, resulting in a diverse range of ecosystems packed into a relatively small area. The country is typically divided into five major geographic regions: the lowland rainforests of the Darién in the east, the central mountain ranges, the Pacific and Caribbean coastal plains, the Chiriquí Highlands in the west, and the offshore islands. Each of these regions harbors unique landscapes, climates, and wildlife, making Panama one of the most ecologically varied destinations in Central America.

The Darién lowlands, located in the easternmost part of the country, are home to some of the most untouched rainforests in Central America. This vast wilderness, which extends into Colombia, shelters a staggering variety of wildlife, including jaguars, harpy eagles, and poison dart frogs. Much of this region remains roadless and is best explored by boat or guided treks. In contrast, the central mountain ranges, including the Cordillera Central, stretch across the country, creating a mix of cloud forests, montane valleys, and ridges. These highlands serve as critical migration corridors for birds and are home to unique herpetofauna, including high-altitude salamanders and endemic snakes. The famed Pipeline Road, located in the foothills near Panama City, provides access to some of the most biodiverse forests in the world.

The Pacific and Caribbean coastal plains offer distinct yet equally rich ecosystems. The Pacific lowlands tend to be drier, with mangrove forests, tropical dry forests, and tidal estuaries that attract shorebirds, crocodiles, and marine turtles. The Caribbean side, in contrast, is wetter and densely forested, with humid tropical rainforests stretching to the coast. These coastal habitats transition into Panama’s offshore islands, which range from the coral-rich archipelagos of Bocas del Toro and Guna Yala to the remote, wildlife-filled Isla Coiba. The Chiriquí Highlands, in western Panama, provide a cooler, cloud-enshrouded retreat, famous for its rich avian life, including the resplendent quetzal, and the montane vipers such as the black-speckled palm-pitviper (Bothriechis nigroviridis) and the side-striped palm-pitviper (Bothriechis lateralis). These varied landscapes make Panama a compelling destination for ecotourists, offering an unparalleled mix of tropical wilderness, coastal beauty, and highland biodiversity.

Political Regions of Panama

Panama is divided into ten provinces and five indigenous comarcas, each with its own unique geography, culture, and administrative governance. The provinces serve as the primary political divisions, much like states in the U.S., while the comarcas are autonomous indigenous territories that maintain distinct cultural traditions and governance structures. This division reflects Panama’s diverse population, which includes both urban centers like Panama City and remote indigenous communities in the rainforests and coastal regions.

The ten provinces are Bocas del Toro, Chiriquí, Coclé, Colón, Darién, Herrera, Los Santos, Panamá, Panamá Oeste, and Veraguas. The Panamá Province, home to the capital, is the economic and political heart of the country. Chiriquí, in western Panama, is known for its cloud forests and highland coffee farms, while Darién, in the east, remains one of the least developed regions, covered in dense rainforests teeming with wildlife. The Bocas del Toro province, along the Caribbean coast, is famous for its island archipelago, attracting ecotourists with its mix of tropical rainforests and coral reefs. Meanwhile, Veraguas is unique as the only province that spans both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, offering diverse landscapes ranging from mountains to mangroves.

In addition to the provinces, Panama recognizes five indigenous comarcas: Guna Yala, Emberá-Wounaan, Ngäbe-Buglé, Madugandí, and Wargandí. These territories are self-governed by indigenous groups, preserving traditional ways of life while also managing natural resources within their regions. Guna Yala, an autonomous coastal territory, is particularly well-known for its string of idyllic islands, the San Blas archipelago, and its rich cultural heritage. Ngäbe-Buglé, the largest comarca, spans multiple provinces in western Panama and encompasses a mix of mountainous and coastal terrain. These indigenous regions are crucial for conservation efforts, as they harbor vast stretches of primary rainforest and serve as vital wildlife corridors for species such as jaguars, harpy eagles, and endemic amphibians. Understanding Panama’s political divisions helps ecotourists navigate the country while also recognizing the importance of indigenous communities in conservation and sustainable tourism.

Panama Weather Patterns:

Best Times for Birding, Herping, and Exploring

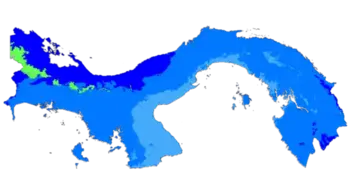

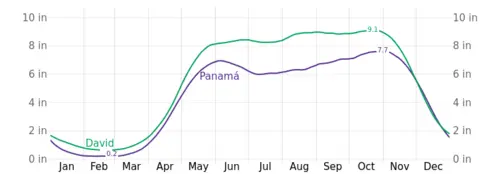

Panama’s climate is tropical and humid year-round, with temperatures generally ranging between 24°C (75°F) and 32°C (90°F) in the lowlands and slightly cooler conditions in the highlands. Unlike temperate regions, Panama does not have four distinct seasons but instead experiences a dry season (December–April) and a rainy season (May–November). The Caribbean coast and Darién rainforest receive significant rainfall year-round, while the Pacific side of the country follows a more pronounced wet-dry cycle. The highland areas, such as Boquete and Cerro Punta, remain cooler and wetter than the lowlands throughout the year.

The rainy season (May–November) is characterized by frequent afternoon showers, high humidity, and lush, green landscapes. This is the best time for herping, as amphibians and reptiles are most active during the wet season. Frogs, snakes, and other herpetofauna are more frequently encountered along forest trails, particularly in regions like Darién National Park, Soberanía National Park, and Gamboa Rainforest. The wet season also marks the fruiting period for many trees, which attracts mammals and birds, making it a great time for birding in lowland rainforests. However, heavy rains can make certain trails inaccessible, especially in remote areas.

The dry season (December–April) brings clear skies, lower humidity, and easier hiking conditions, making it an excellent time for general wildlife viewing, particularly in highland cloud forests and drier lowland areas. Birds are easier to spot in the open canopy, and migratory species from North America add to the diversity during these months. While herping activity slows in drier habitats, riverbanks, ponds, and moist microhabitats remain productive. This season also coincides with turtle nesting along the Pacific coast, offering opportunities to witness olive ridley and leatherback turtles coming ashore to lay eggs. Ultimately, both seasons have advantages, and choosing the right time depends on the species and habitats an ecotourist hopes to explore.

Panama's rainfall patterns vary significantly by region due to its geography, prevailing winds, and proximity to both the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. The Caribbean side is generally wetter than the Pacific, receiving 2,500 to 5,500 millimeters (98 to 217 inches) of rainfall annually, with some areas—like Bocas del Toro and the Darién rainforest—experiencing rain year-round. The Darién lowlands, one of the wettest regions in the country, can receive over 6,000 millimeters (236 inches) of rainfall annually, supporting dense, biodiverse rainforests. Meanwhile, the highlands, including Cerro Punta and Boquete, receive 3,000 to 5,000 millimeters (118 to 197 inches) per year, with frequent mist and cloud cover contributing to a cool, humid environment ideal for cloud forest species.

In contrast, the Pacific lowlands experience a more defined dry season, with annual rainfall ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 millimeters (39 to 118 inches). The Azuero Peninsula, located in the Pacific southwest, is the driest part of the country, receiving as little as 1,000 millimeters (39 inches) annually, creating a unique dry tropical forest ecosystem. Panama City and the central lowlands receive 1,500 to 2,500 millimeters (59 to 98 inches) per year, with most of this falling between May and November. Islands like Coiba and the Pearl Islands, though surrounded by ocean, still experience significant rainfall, particularly during the wet season, supporting tropical rainforest ecosystems. Understanding these rainfall differences is essential for ecotourists planning their trips, as some regions become inaccessible due to flooding in the wet season, while others provide prime wildlife viewing opportunities.

Panama’s Rich Biodiversity:

A Guide for Birders, Herpers, and Wildlife Photographers

Panama is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, serving as a crucial biological corridor between North and South America. With over 10,000 species of plants, nearly 1,000 bird species, and more than 400 species of amphibians and reptiles, Panama’s wildlife is extraordinarily diverse for a country of its size. This immense biodiversity is due in part to its varied ecosystems, ranging from lowland rainforests and cloud forests to mangroves, dry tropical forests, and extensive coastal habitats. Additionally, Panama’s position between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans has fostered marine biodiversity unlike anywhere else in Central America. The country’s geographic location as an ecological bridge has resulted in a fascinating mix of North American and South American fauna, making it a prime destination for ecotourists, herpers, and wildlife photographers.

Panama’s lowland rainforests, such as those found in Darién National Park, Soberanía National Park, and La Amistad International Park, are teeming with tropical amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. These humid forests are home to poison dart frogs, vine snakes, eyelash vipers, and rare species like the Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki). Mammals such as jaguars, ocelots, and tamanduas also thrive here. In contrast, the mountain rainforests and cloud forests of Chiriquí and El Valle de Antón feature cooler temperatures and persistent mist, providing habitat for highland specialists like the resplendent quetzal, glass frogs, and unique cloud forest reptiles. These forests transition into tropical dry forests along the Pacific slope, where species like boa constrictors, spiny-tailed iguanas, and deer are more common.

Panama’s mangrove forests and coastal wetlands, such as those in the Gulf of Chiriquí and Bocas del Toro, are critical breeding grounds for marine life, crocodiles, wading birds, and shorebirds. The country’s two coasts—the Caribbean and the Pacific—support distinct marine ecosystems, with coral reefs, seagrass beds, and rocky shorelines providing habitat for sea turtles, rays, reef sharks, and a variety of tropical fish species. Offshore, Coiba National Park is home to whale sharks, humpback whales, and some of the healthiest coral reefs in the eastern Pacific. This remarkable diversity of ecosystems and species makes Panama one of the best destinations for nature enthusiasts seeking to photograph or observe wildlife in its many natural habitats.

Discovering Panama’s Ecosystems:

Rainforests, Cloud Forests, and More

Panama’s ecosystems are remarkably diverse for such a small country, spanning two coasts, two oceans, and a steep mountain spine that creates dramatic climatic contrasts. Along the Caribbean lowlands, lush tropical rainforests thrive under constant humidity and rainfall, forming part of the greater Chocó–Darién bioregion—one of the most biodiverse areas on Earth. These forests are home to jaguars, harpy eagles, poison dart frogs, and countless orchids and bromeliads. In contrast, the Pacific slope supports drier tropical deciduous forests and mangroves adapted to pronounced wet and dry seasons. As elevation rises through the Cordillera Central and Cordillera de Talamanca, the landscape transitions into montane and cloud forests, where moss-draped oaks, tree ferns, and epiphytes flourish in perpetual mist. These highland forests—particularly around Boquete, Volcán Barú, and Santa Fé—harbor resplendent quetzals, howler monkeys, and an extraordinary diversity of amphibians. In the far west and east, wetlands, swamps, and coastal mangrove systems provide vital breeding grounds for fish, reptiles, and birds, while coral reefs and seagrass beds fringe both the Caribbean and Pacific shores. This mosaic of habitats—ranging from lowland rainforest to misty peaks—makes Panama a microcosm of tropical biodiversity, where ecosystems change dramatically within a few hours’ drive.

Panama’s Iconic Wildlife:

Essential Sightings for Herpers, Birders, and Ecotourists

Panama is home to an extraordinary array of amphibians and reptiles, making it a prime destination for herpers. Among the most sought-after species are poison dart frogs, which thrive in the country’s humid forests. These including several color morphs of the strawberry poison dart frog (Oophaga pumilio), found in the Caribbean lowlands, and the critically endangered Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki), an iconic species of the cloud forests. Panama is also home to some of the most beautiful palm pitvipers, including the black-speckled palm viper (Bothriechis nigroviridis), an elusive, montane species, as well as the eyelash pit viper (B. nigroadspersus formerly B. schlegelii), and the Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys), each with its own unique coloration and habitat preference. Other fascinating reptiles include giant anoles, vine snakes, and boa constrictors, while crocodilians like the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) lurk in Panama’s freshwater rivers and mangrove swamps.

For birders, Panama is an unrivaled hotspot with nearly 1,000 species, including some of the most spectacular birds in the Neotropics. The country’s cloud forests, particularly in Boquete, El Valle de Antón, and La Amistad International Park, are prime locations for spotting the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno), an iridescent green-and-red bird revered by indigenous cultures. Other cloud forest specialties include long-tailed silky-flycatchers, collared trogons, and a variety of tanagers. The lowland rainforests of Soberanía National Park and the Darién teem with toucans, parrots, motmots, and manakins, while the vast mangroves and coastal regions host ibises, herons, and raptors like the crested eagle. Panama’s legendary Pipeline Road, just outside Panama City, is one of the world’s top birding destinations, offering a chance to see rare species such as the rufous-vented ground-cuckoo and black-crowned antpitta.

Panama’s mammalian diversity is equally impressive. Forested areas are home to two species of sloths—the brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus) and the Hoffmann’s two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni), both of which are frequently spotted hanging from rainforest canopies. Tamanduas (small tree-climbing anteaters), agoutis, ocelots, and jaguarundis roam Panama’s jungles, while the deeper forests of Darién National Park still shelter elusive jaguars and harpy eagles. Along Panama’s coasts, visitors can witness nesting sea turtles, including the leatherback, hawksbill, olive ridley, and green sea turtles, which return each year to lay their eggs on beaches like Playa La Barqueta and Isla Cañas. Whether exploring the treetops for quetzals, searching for dart frogs on the forest floor, or witnessing sea turtles nesting on moonlit beaches, Panama offers countless opportunities for unforgettable wildlife encounters.

Local Culture and Language

Understanding Panamanian Culture and Traditions as an Ecotourist

Panama’s cultural identity is shaped by a rich blend of Indigenous, Spanish, Afro-Caribbean, and North and South American influences, making it one of the most diverse countries in Central America. The country’s Indigenous heritage remains strong, with groups like the Guna, Emberá, Ngäbe-Buglé, and Wounaan preserving their languages, crafts, and traditions. The Guna Yala comarca, a semi-autonomous region along the Caribbean coast, is famous for its mola textiles, intricate hand-sewn panels that reflect Guna cosmology and storytelling. The Emberá people, primarily residing in the Darién rainforest and along Panama’s rivers, maintain a deep connection with nature, incorporating sustainable practices into their daily lives. Many Indigenous communities welcome visitors, offering a unique opportunity to learn about traditional forest medicine, handicrafts, and ancient ways of life that align with the values of ecotourism.

Spanish colonization left a lasting mark on Panama, particularly in its architecture, religious traditions, and language. The majority of Panamanians are Spanish-speaking and Catholic, with major festivals like Carnaval, Semana Santa (Holy Week), and Fiesta Patrias (Independence Day celebrations) playing a significant role in national culture. However, unlike many Latin American nations, Panama has a strong Afro-Caribbean influence, particularly along the Caribbean coast in cities like Colón and Bocas del Toro. These regions were historically settled by Afro-Caribbean laborers who arrived during the construction of the Panama Canal and railroad, bringing with them English Creole, reggae, calypso, and Caribbean cuisine, which remain deeply ingrained in local culture. This fusion of cultures creates a lively and welcoming atmosphere for visitors, particularly in Panama City, where modern cosmopolitanism meets deep-rooted traditions. Ecotourists will find that Panama’s cultural diversity is just as fascinating as its biodiversity, offering opportunities to engage with vibrant local communities in both urban and rural settings.

Understanding and Respecting Local Customs

As in any country, understanding and respecting local customs enhances the travel experience and fosters positive interactions between visitors and locals. While Panamanians are generally friendly and accustomed to international travelers, especially in major tourist areas, cultural etiquette varies depending on the region. In rural and Indigenous communities, modest dress and polite behavior are expected, and it is customary to greet locals with a friendly "Buenos días" (Good morning) or "Buenas tardes" (Good afternoon). When visiting an Indigenous village, it is respectful to ask permission before taking photographs, as some communities have cultural or spiritual beliefs tied to images. Additionally, many Indigenous groups rely on handicrafts and eco-tourism initiatives for income, so purchasing goods directly from artisans is a meaningful way to support their traditions.

Environmental respect is another crucial aspect of Panamanian culture, particularly in protected areas and national parks. Many local communities depend on ecotourism, and visitors are encouraged to practice Leave No Trace principles, avoid disturbing wildlife, and follow local conservation guidelines. In marine environments, such as Bocas del Toro and the Pearl Islands, it is important to respect coral reefs, avoid collecting shells or wildlife, and be mindful of nesting sea turtles. While Panama’s urban areas, such as Panama City and David, are more relaxed in terms of social etiquette, taking the time to learn about local customs and showing appreciation for Panamanian traditions—whether through language, respectful behavior, or environmental stewardship—will be greatly valued by locals.

Is it Acceptable to Wear Revealing Clothing in Panama?

Whether you're at the beach or in the sweltering hot rainforests, you'll be tempted to dress down, but is revealing Western fashion acceptable in Panama? For the most part, the answer is yes. In urban areas and tourist hotspots like Panama City, Bocas del Toro, and beach resorts along the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, it is perfectly acceptable for women to wear bikinis, tube tops, tank tops, short shorts, and other revealing clothing. Panamanians, particularly in these areas, are accustomed to Western fashion, and you’ll find that locals and visitors alike dress comfortably in warm-weather attire. Bocas del Toro, in particular, has a laid-back, Caribbean vibe where beachwear is the norm.

However, in rural areas, Indigenous communities, and more conservative towns, dressing modestly is recommended out of respect for local customs. For example, in small villages, Indigenous comarcas (such as Guna Yala or Ngäbe-Buglé), and religious sites, women typically dress more conservatively, and wearing sports bras or very revealing outfits in non-beach settings may be seen as inappropriate. While tank tops and shorts are generally fine, covering up slightly with a lightweight dress, sarong, or t-shirt is advisable when visiting these areas.

If you plan to explore hiking trails, rainforests, or national parks, it’s also practical to wear light, breathable clothing that provides sun and insect protection, as some trails can be humid and home to biting insects. Overall, while beachwear is acceptable at beaches and tourist destinations, being mindful of local customs in more traditional areas will ensure a respectful and comfortable experience.

Do You Need to Know Spanish for Your Panama Ecotourism Adventure?

While it is possible to visit Panama without speaking Spanish, having some basic knowledge of the language will significantly enhance your experience, especially if you plan to explore areas outside of Panama City, Bocas del Toro, and major tourist destinations. In Panama City, many people working in hotels, restaurants, and tourist services speak at least basic English, as the city has strong ties to international business and tourism. Similarly, in Bocas del Toro and Colón, where there are strong Afro-Caribbean and expat communities, English is commonly spoken, particularly in businesses catering to tourists.

However, once you venture into more rural areas, national parks, and Indigenous communities, English is far less commonly spoken. Panama is less "touristy" than Costa Rica, and consequently, English is not as common. In places like Darién, the highlands of Chiriquí, or local markets outside of tourist zones, it is highly beneficial to know some basic Spanish phrases for communication. Simple phrases like “¿Dónde está…?” (Where is…?), “¿Cuánto cuesta?” (How much does it cost?), and “Gracias” (Thank you) can go a long way in making interactions smoother. Many Panamanians are patient and appreciate any effort to speak Spanish, even if it’s just a few words.

If you are an ecotourist, herper, or wildlife photographer hiring local guides, many professional guides do speak English, particularly in Soberanía National Park, Gamboa, and Boquete, where eco-tourism is well-established. However, guides in more remote areas may only speak Spanish, so having a translation app or phrasebook can be helpful. Overall, while knowing Spanish is not required for visiting Panama, learning a few key phrases will enhance your travel experience, help with navigation, and allow for more meaningful interactions with locals.

Downloading Google Translate to your phone for quick reference is strongly recommend. Panamanians are usually patient while you type in a translation, and many use the app themselves! Below, you'll find a table of key phrases and nouns that should come in handy in Panama.

Spanish Terms to Learn

| English | Spanish | Comment |

| I want | Yo queiro | You can drop the “Yo”, which means “I”, and simply say “quiero”, since the “I” is implied with this particular conjugation. |

| I need | Yo necisito | Or, simply just, "Necisito" |

| Yes | Sí | |

| No | No | |

| The | El/La/Los | Masculine/Feminine/Plural |

| Please | Por favor | |

| You're welcome | De nada | Con gusto, which translates to “with pleasure” is another popular way of saying "you're welcome". |

| To go to | ir a | Example: "Yo necesito ir a Lima" ↦ "I need to go to Lima". |

| Bus stop | Parada de autobús | Often, people will shorten it to “La parada” |

| Bus station | Estación de autobuses | |

| Taxi | Taxi | |

| Airport | Aeropuerto | |

| My suitcase | Mi maleta | |

| My passport | Mi pasaporte | |

| Ticket (bus) | Boleto | |

| Ticket office | Boletería | Look for the "Boletería" sign at bus stations. This is where you buy your bus ticket. |

| Bathroom | Baño | Bathroom, washroom, lavatory, latrine, water closet, or whatever you call the place with the toilet. |

| Where is the... | Dónde está el... | Example: "Where is the bathroom?" ↦ "Dónde esta el Baño". Note that está may not be the correct conjugation for what follows, and el may need to be replaced with la or los for propper grammar. However, most spanish speakers will still understand you even if your grammer ain't no good. |

| How much money | Cuánto dinero | |

| Left (direction) | Izquierda | A la izquierda means "on the left" or "to the left" |

| Right (direction) | Derecha | "La Derecha" means "on the right" or "to the right" |

| Close | Cerca | Example: "El hotel esta cerca" ↦ "The hotel is close" |

| Here | Aquí | Example: "Esta aquí" ↦ "It is here" |

| Sir | Señor | |

| Madam/Madame/Ma'am | Señora | |

| Excuse me (to get attention) |

Disculpe | Disculpe is used to get someone's attention, e.g. "Disculpe Señor" ↦ "Excuse me sir" or as a preemptive "excuse my behavior" like when you are passing through a crowd. |

| Excuse me (to appologize) |

Perdón | Perdón is used as a polite way to excuse minor infractions such as accidentally bumping into someone. |

| I'm sorry | Lo siento | Overuse of “sorry” is sometimes viewed as sounding disingenuous to some Spanish speakers. In the U.S. we often use “sorry” in a non serious way to mean “excuse me” or “my bad”, whereas other cultures view “sorry” in a more serious way, meaning “I am truly sorry, repentant, and ashamed of my actions”, and thus, saying "sorry” for trivial things like accidentally bumping into someone, may sound overly dramatic and phony. |

| My name is | Me llamo | "Mi nombre es" also means "my name is" |

| What is your name? | Cómo te llamas | |

| Do you speak english? | Hablas inglés | |

| I don't understand | No entiendo | |

| Hotel | Hotel | |

| Food/Meal | Comida | |

| Dinner/Supper | Cena | |

| Breakfast | Desayuno | |

| Coffee | Café | "Taza de café ↦ "Cup of coffee" |

| Tea | Té | |

| Water | Agua | "Vaso de agua" ↦ "Glass of water" |

| More | Más | "Más agua por favor" ↦ "More water please" |

| I need to hike at night | Necesito caminar de noche | If you're a herper, this will likely come up. |

| Snake | Serpiente | Culebra also means "snake". Culebra sometimes refers to small snakes in particular. |

Preparing for Your Panama Adventure

Essential Travel Documentation for Ecotourists in Panama

Short-Term Visitors (Stays up to 90–180 Days)

Visa & Entry Duration: Citizens of the United States and Canada can visit Panama visa-free for up to 180 days (approximately 6 months) as tourists (Visa Policy of Panama). Travelers from Australia, European Union member countries, the UK, and most other European nations also do not need a visa for tourist visits, but their stay is limited to 90 days (3 months) maximum (Visa Policy of Panama). Upon arrival, eligible visitors receive an entry stamp in their passport (no separate tourist visa or card is required for these nationalities under normal circumstances). Panama does not issue a physical “tourist card” for visa-exempt visitors arriving by air – the passport entry stamp serves as the permit. (An entry permit fee is only required for certain cases, such as private yacht travelers, who must pay a maritime entrance fee and obtain a short-term cruising permit U.S. Department of State.)

- Passport Validity: You must present a valid passport – Panama requires at least 3 months validity beyond your entry date Wikipedia. (In practice, it’s recommended to have 6 months validity remaining on your passport to avoid any issues tourismpanama.com.) Your passport will be stamped on entry; always carry it (or a copy) with you in Panama as local authorities may request ID showing your entry stamp travel.state.gov.

- Proof of Onward Travel: Proof of a return or onward ticket is mandatory. At immigration, you must show a paid round-trip ticket or onward ticket out of Panama, demonstrating you intend to leave before your allowed stay ends travel.state.gov.. For example, U.S. and Canadian citizens should have a ticket dated within 180 days of entry, and Australians/Europeans within 90 days. Airlines may check this before boarding as well.

- Proof of Sufficient Funds: Visitors need to prove financial solvency for their trip. At least $500 USD (cash or equivalent) per person is required. You can satisfy this by showing cash, a bank statement or letter, credit card with a recent statement, travelers’ checks, or similar proof that you have access to at least $500 (Panamanian officials may ask to see this). (Some sources note $500 is the typical requirement, though certain nationalities or longer stays might be asked for a higher amount.) Note that most western tourists report not being asked to show proof of sufficient funds. Sources: travel.state.gov, tourismpanama.com.

- Entry Stamp & Tourist Permit: For visa-exempt nationalities (U.S., Canada, Europe, Australia, etc.), no prior visa or tourist card is needed – you will receive a tourist entry stamp on arrival. This stamp notes the date of entry (and sometimes hand-written duration). Ensure immigration stamps your passport properly upon entry. If arriving by commercial flight, no additional tourist permit is required. (As a special case, travelers arriving by private boat must pay a $110 entry permit which grants a 3-month stay, extendable with immigration authorities up to 2 years if needed.) There is no routine “tourist card” purchase for most travelers – Panama phased out the old tourist card system for visa-waiver visitors. Source: travel.state.gov

- Health and COVID-19 Requirements: As of the latest updates, Panama has no COVID-19 test or vaccination requirement for entry. Travelers do not need to show COVID vaccination certificates or test results at this time (policies are subject to change, so checking before travel is wise). However, other health rules apply: if you are arriving from a country with yellow fever risk (e.g. Brazil), Panama requires proof of Yellow Fever vaccination given at least 10 days before entry. (This applies to travelers who have been in countries like Brazil, not to those coming directly from the U.S./Canada/Europe unless they transited through a risk area.) Apart from that, basic travel health precautions (e.g. travel insurance, up-to-date routine vaccines) are recommended but not officially required for entry. Source: tourismpanama.com

- Other Entry Requirements: Panama reserves the right to deny entry to persons with serious criminal records or a history of deportation from Panama. Immigration officers have discretion to question travelers about their visit’s purpose and finances. It’s helpful to know the address of your lodging and have a rough travel itinerary, as you may need to fill this on the entry form or answer the officer. Visitors should remember that as tourists they cannot work in Panama (employment requires a work permit/visa). Driving is allowed with a foreign license for up to 90 days only (even if your visa-free stay is 180 days, you must obtain a Panama driver’s license if staying beyond 90 days and intending to drive). Sources: tourismpanama.com, Smithsonian

Long-Term Visitors (Stays Beyond the Standard Tourist Period)

If you wish to stay in Panama longer than the 90-day or 180-day tourist allowance (for an extended vacation, remote work, or other personal travel without establishing residency or employment in Panama), there are additional requirements and restrictions to be aware of. Panama does not simply allow tourists to extend their stay beyond 90/180 days by default – you must take formal steps to remain longer. These details are beyond the scope of this travel guide, but more information can be found at NDM, Smithsonian, Migracion.gob.pa, and Legal@work.

Summary: Tourists from the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Australia can enjoy Panama visa-free for short stays (90 or 180 days depending on nationality) provided they have a valid passport (with ≥3 months validity), a return ticket, and evidence of at least $500 funds. No tourist visa or card is needed for these short visits, and there are currently no COVID-19 entry restrictions. For those wishing to stay beyond the standard period without working or immigrating, advance planning is required – you must either apply for an appropriate short-term visa or residency program, and furnish additional documentation like a police background check and further proof of solvency. Simply leaving and re-entering to extend your stay is risky and not assured. By securing the proper visa or extension, long-term visitors can remain in Panama legally and enjoy an extended tropical stay while meeting all requirements. Always verify the latest rules with official sources (Panama’s National Migration Service or a Panamanian consulate) before your trip, as regulations can update frequently

Sources: Panamanian immigration regulations and official guidance; U.S. Department of State – Panama Entry Requirements; Panama Tourism Authority guidelines; Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute advisory (Panama); and Panama immigration law firms’ summaries.

Safety

Panama is generally considered a safe destination for travelers, with a U.S. State Department travel advisory level of 2, which encourages visitors to "exercise increased caution." This advisory highlights some risks but is not a recommendation against travel to the country. Most visitors have a trouble-free experience, whether in urban, rural, our tourist areas. However, travelers should be wary that they may be targeted for petty theft. Always keep a close eye on your belongings, keep your passport and valuables close, and don't invite trouble, like unnecessary flaunting of valuables in public sight, public intoxication, walking alone at night.

The U.S. State Department advises travelers to exercise caution in certain regions of Panama, particularly the Darién Province and the Mosquito Gulf, due to their remoteness and the presence of criminal organizations, including narco-traffickers and smugglers. These areas are largely inaccessible by road, with most travel occurring by river or air, and are considered unsafe for tourists. In coastal zones, particularly along remote beaches, packages of narcotics have occasionally been found washed ashore, and travelers are warned not to touch or move these items and to report them to local authorities. Panama’s beach conditions can also be hazardous, with strong currents and few lifeguards, contributing to occasional drownings. Boaters should remain vigilant, as maritime search and rescue capabilities are limited, and criminal activity is known to occur along some coastal routes.

Crime is a concern in urban areas such as Panama City, Colón, and parts of Chiriquí Province, where thefts, armed robberies, and occasional violent crimes have been reported. Tourists are advised to take standard precautions, such as securing valuables, locking car doors, and using only licensed taxis. Demonstrations are relatively common throughout the country and may cause road closures, even in popular tourist areas. While typically non-violent, protests can escalate and lead to police responses involving tear gas. The tourism industry in Panama is not uniformly regulated, and safety standards for activities, guides, and equipment vary widely, especially outside major cities. Emergency medical services are limited in rural areas, and visitors are strongly encouraged to carry medical evacuation insurance and understand the risks associated with adventure travel in remote parts of the country.

Vaccinations for Traveling to Panama

When planning a trip to Panama, especially as an ecotourist visiting remote natural areas, it’s wise to consider both official vaccine recommendations and practical risk levels based on where you’re going, how long you’ll be staying, and what kind of activities you’ll engage in. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and Panama’s Ministry of Health all offer general guidance, but individual choices often vary based on a traveler’s health history, destinations, and tolerance for risk. Here's a breakdown of the most cautious versus more practical approaches, and what most travelers typically choose.

Essential Vaccines – Routine and Entry-Related

All travelers to Panama should be up to date on routine vaccinations, which include:

- MMR (Measles-Mumps-Rubella)

- DTP (Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis)

- Polio

- Influenza (seasonal flu)

These are considered baseline immunizations and while they are not mandatory, they are strongly recommended by all health authorities regardless of travel plans.

Additionally, Yellow Fever vaccination is required only if you are arriving from a country where Yellow Fever is endemic, such as Brazil. If you're flying directly from the U.S., Canada, Europe, or Australia, it’s not mandatory. However, if your itinerary includes travel to or transit through a Yellow Fever risk country, proof of vaccination is required for entry into Panama, and you must receive the vaccine at least 10 days prior to arrival.

Recommended Vaccines – Varying by Itinerary and Risk Tolerance

The CDC and WHO recommend the following vaccines for travelers to Panama, but whether you should get them depends on your destinations and level of exposure:

-

Hepatitis A: Strongly recommended for all travelers, even those staying in urban areas or tourist resorts, due to potential contamination of food or water.

- Practical: Most tourists opt to get this shot. Effective for many years, and recommended for other tropical countries, so if you plan on traveling elsewhere in the tropics, this shot is a good investment.

- Cautious: Essential for anyone traveling off the beaten path or eating street food.

-

Typhoid: Recommended for travelers who will spend time in rural areas, eat adventurously, or stay in local homes. Available as an oral or injectable vaccine.

- Practical: Many wildlife travelers and herpers get this, especially if visiting villages or rainforest lodges. Affordable, long-lasting vaccine useful throughout the tropics.

- Cautious: Advised for all but the most urban, short-term visitors.

-

Hepatitis B: Recommended for longer stays, healthcare workers, or anyone who might need medical care in Panama, or engage in activities that involve blood or body fluids.

- Practical: Often skipped for short-term travelers unless they’re combining this trip with others to similar regions.

- Cautious: Worth considering if you travel frequently in Latin America.

-

Rabbies: A precautionary vaccine for travelers doing extensive outdoor activities, especially in remote areas where medical care is limited. Panama has bats and mammals that can carry rabies.

- Practical: Rarely chosen by most tourists due to cost and inconvenience (3 pre-exposure shots), unless visiting for extended fieldwork or living rurally.

- Cautious: Advised for cavers, field biologists, long-stay ecotourists, and wildlife (mammal) handlers.

-

Malaria prophylaxis: Panama has limited malaria risk, mainly in Darién, Guna Yala (San Blas Islands), and some rural Caribbean areas. The risk is low to moderate, and malaria prophylaxis is not typically recommended for visits to Panama City, Bocas del Toro, Boquete, or other well-developed areas.

- Practical: Most travelers do not take anti-malarials, especially if avoiding high-risk zones.

- Cautious: Consider if you're traveling to remote Indigenous territories or jungle areas near the Colombia border for extended periods.

Travelers often have mixed opinions about malaria pills. These are generally expensive and can have side effects. While malaria is present throughout the tropics, Malaria can be highly localized, meaning the risk varies significantly depending on the exact travel destination. Therefore, travelers should attempt to find out if malaria is common in the areas they are traveling to or through, if possible. Regardless of the presence of malaria or other mosquito tramsmitted diseases, travelers should take precautions to minimize exposure to mosquito bites. Mosquito prevention measures such as using DEET-containing repellents and treating clothing and gear with permethrin (available at outdoor outfitters like REI or the camping sections of big-box stores like Walmart) are essential.

What Most Travelers Do

Most short-term visitors, including tourists visiting Panama City, the Canal Zone, Boquete, Bocas del Toro, or the Pacific beaches, get Hepatitis A and stay up to date on routine vaccines, but skip Typhoid, Rabies, and malaria pills. Those heading to rainforest areas—especially herpers, birders, and backpackers—often add Typhoid, and in some cases Hepatitis B. Rabies vaccination is more common among field researchers and ecotourists doing multi-week stays in remote areas. Malaria prophylaxis is only taken by a minority of travelers due to the localized and low incidence.

Final Notes on Vaccines for Panama

It's best to consult a travel medicine clinic at least 4–6 weeks before departure, as some vaccines require multiple doses or take time to become effective. If your itinerary includes high-risk zones (like the Darién), or you're doing fieldwork, herping, or jungle trekking, consider following the more cautious route. If you’re sticking to popular destinations, a practical vaccine plan will be sufficient and in line with what most travelers opt for.

It’s important to note that the above recommendations are based on my personal (nonprofessional) experience, research, and risk tolerance, and may not reflect the views of the CDC or the broader medical community. All travelers should conduct their own research, consult resources like the CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) websites, and seek advice from a specialized travel clinic (such as Passport Health in the U.S.) which offers expert guidance tailored to specific travel destinations. Ultimately, the choice of what precautions to take are up to you and depend on your own risk tolerance.

Travel Insurance and Health Considerations

When planning your trip to Panama, it’s crucial to consider travel insurance and health-related preparations to ensure a safe and worry-free experience. Although Panama is generally a safe destination, unforeseen circumstances such as accidents, illness, or travel disruptions can occur anywhere. The quality of health care can vary significantly outside of major cities like Panama City and David. Tourists visiting remote regions should be aware of the travel time to the nearest hospital and have a plan for accessing emergency medical assistance.

Securing comprehensive travel insurance that covers medical expenses, trip cancellations, and other potential issues provides peace of mind and is highly recommended, even for budget travelers. Travel insurance is relatively inexpensive and should be considered essential for all travelers. I personally use Allianz travel insurance. While I’ve been fortunate never to have made a claim and thus cannot speak to the claims process, acquiring the insurance was straightforward and affordable, offering excellent coverage and benefits. They also provide a concierge telephone service that can assist with disrupted travel plans and offer advice on entertainment, accommodations, currency exchange, and more.

Can You Drink the Tap Water in Panama?

In most of Panama, particularly in urban and developed areas, tap water is generally safe to drink, and the country is considered to have one of the most modern and reliable water systems in Central America. As a comparison, Panama's water is arguably safer overall than Costa Rica's, which is regarded as relatively safe. Panama City, the Canal Zone, Boquete, and David have well-treated municipal water that meets international safety standards. Many locals and expats drink the tap water without issue in these areas, and travelers often do the same without complications. Additionally, most hotels, eco-lodges, and tourist services in these areas source water from treated supplies or offer filtered water for guests.

That said, caution is warranted depending on where you travel within Panama. In rural areas, particularly in the Darién, Guna Yala (San Blas Islands), remote mountain villages, and Indigenous comarcas, the water may come from untreated local sources or rainwater catchment systems. These are not always reliably filtered or disinfected, and even if locals drink it without consequence, foreign visitors may be more susceptible to gastrointestinal issues from unfamiliar microbes. In such regions, it's safer to drink bottled water, use a reliable filter or UV sterilizer, or request purified water provided by lodges or guides. When in doubt, especially during extended nature travel, boil or treat your water before drinking.

Food: Groceries and Restaurants

Grocery shopping in Panama is convenient and familiar for most travelers, especially in urban areas and well-developed tourist hubs. Large supermarket chains like Riba Smith, El Rey, Super 99, and PriceSmart are found throughout Panama City, David, Boquete, and Coronado, offering a wide selection of local and imported products. Riba Smith, in particular, is known for its extensive selection of North American and European goods, making it a favorite among expats and visitors craving familiar items. PriceSmart, a membership-based wholesale store similar to Costco, is ideal for those staying longer or traveling in groups. For fresh produce and local flavor, municipal markets and roadside fruit stands are common across the country, especially in smaller towns and rural areas. These local options often sell tropical fruits, vegetables, eggs, and freshly made tortillas or tamales at much lower prices than supermarkets, offering a more immersive and budget-friendly shopping experience.

Grocery costs in Panama are generally comparable to or slightly lower than in the U.S., depending on what you buy. Local products like fish, rice, beans, plantains, yucca, pineapples, and bananas are inexpensive and widely available, while imported goods, cheese, and specialty items can be significantly more expensive due to import taxes. Imports such as mosquito repellent, sun screen, and certain hygeine items that are more popular amongst travelers than the locals will also likely be pricier in Panama, and travelers should consider purchasing these items in their home country and packing them. Meat and dairy tend to vary in quality and price, with chicken and pork being more affordable than beef or imported cheeses. Travelers looking to self-cater—especially those staying in Airbnbs, ecolodges with kitchens, or for extended periods—can eat well on a modest budget by shopping at local markets and sticking to Panamanian staples. However, if you're looking for organic products, gluten-free items, or international brands, expect to pay a premium and find them primarily in larger cities.

Dining out in Panama ranges from inexpensive fondas (local diners) to high-end restaurants with international menus. Fondas and roadside eateries are scattered throughout the country and serve classic Panamanian dishes such as arroz con pollo (chicken with rice), sancocho (chicken soup), carne guisada (stewed beef), fried plantains, and beans, typically priced between $3 and $7 USD. These are great places to experience everyday Panamanian cuisine at affordable prices. In tourist areas like Bocas del Toro, Boquete, and Panama City, you'll also find a wide variety of international options, including Italian, Indian, sushi, vegan cafés, and high-end fusion restaurants, especially in Panama City’s Casco Viejo and business districts. Prices at mid-range and upscale restaurants are closer to U.S. levels, with entrees often ranging from $10 to $25, but the quality and creativity—particularly in Panama City’s culinary scene—can be well worth it. Whether you’re traveling on a shoestring or seeking a gourmet experience, Panama’s food scene offers something for everyone.

Food safety in Panama varies depending on where you eat, but in general, restaurants that cater to tourists and locals in urban or well-traveled areas maintain acceptable hygiene standards. High-end restaurants, especially in Panama City, Boquete, and Bocas del Toro, adhere to international food safety protocols, use filtered water in food preparation, and typically serve fresh, well-handled ingredients. Mid-range restaurants and tourist-focused cafés are also generally safe, though cleanliness standards can vary slightly—it's wise to look for places with high customer turnover and good online reviews. Fondas, or small local diners, offer hearty and inexpensive meals, and while many maintain good kitchen hygiene, they may not meet the same standards as more formal establishments. When eating at fondas, it’s a good idea to choose busy spots where food is clearly being cooked fresh and turnover is high. Street vendors, while a great way to try authentic Panamanian snacks like empanadas or tamales, come with more risk; hygiene practices vary widely, and refrigeration or handwashing facilities may be limited. That said, many travelers safely enjoy street food in Panama by sticking to stalls with a steady stream of local customers and avoiding items that have been sitting out for long periods or appear undercooked. Travelers with sensitive stomachs should be cautious when eating at small restaurants—not necessarily due to food contamination, but because a sudden change in diet can sometimes lead to stomach upset or diarrhea.

Packing Tips for Ecotourists in Panama

Panama’s compact size belies its incredible environmental diversity—from humid lowland rainforests and Caribbean mangroves to cool highland cloud forests and sun-drenched beaches. Packing appropriately is essential, especially for travelers focused on wildlife photography, birding, or herping, as conditions vary significantly by region and season. While the lowlands are consistently hot and humid year-round, the highlands (like Boquete and El Valle de Antón) can be surprisingly cool, especially at night or during the rainy season. The Caribbean coast and rainforest regions experience rainfall even in the so-called "dry" season, while the Pacific side has a more defined dry season from December to April. If you're venturing into remote reserves like Darién or the cloud forests of Chiriquí, pack with rugged, wet, and variable conditions in mind.

For lowland jungle adventures—whether you're herping in Gamboa or birding along Pipeline Road—you’ll want to be prepared for constant moisture. Rain, sweat, and wet foliage are daily companions in the field. Bring quick-drying synthetic or wool clothing, and avoid cotton, which takes forever to dry in high humidity and can become uncomfortable. Long-sleeved shirts and lightweight hiking pants not only offer protection from mosquitoes and sun, but also help guard against itchy brush and biting ants. A lightweight, packable poncho is highly recommended—it’s the best quick-coverage solution for sudden downpours. While getting a little wet is often unavoidable in Panama’s rainforest, staying comfortable and protecting your gear is critical. A dry bag is essential for storing cameras, electronics, passports, and other sensitive items. Smaller zip-top plastic bags and waterproof packing cubes can help you organize and add a second layer of protection inside your backpack. For travelers moving between regions, layering is key—a light fleece or down jacket comes in handy in the cooler highlands, especially at night, while moisture-wicking base layers and breathable rain gear will serve you well in the jungle.

Footwear is also important: water-resistant hiking shoes or lightweight jungle boots are ideal for muddy trails, while rubber boots are often provided by lodges in swampy areas or can be purchased locally. For general comfort, sandals or quick-drying camp shoes are great for downtime. Don’t forget sun protection (hat, sunglasses, and reef-safe sunscreen), a headlamp or flashlight for night hikes, and insect repellent with DEET or picaridin, especially for herping after dark. With the right gear, you'll be free to focus on what really matters—exploring Panama’s extraordinary biodiversity in comfort and safety.

Rubber boots are essential for rainy season hikes in the rainforest. I recommend pairing them with knee-high, thin wool socks, which prevent the boots from rubbing on skin and allow you to wear shorts for breathability while keeping your legs protected. Wool socks dry quickly and insulate better when wet than cotton socks. Alternatively, long pants tucked into or over the boots work well, provided you use sturdy ankle-high socks (take caution to avoid zippers and cinches being tucked into the boots). At higher elevations, such as the cloud forests of the highlands, where the air is cooler, it’s easier to stay dry, and you’ll want to prioritize warmth. Synthetic fiber clothing and a reliable poncho or rain jacket will help you stay comfortable. Rubber boots may not be necessary on popular, well-maintained cloud forest trails, as they tend to drain better and are more rock than clay, but can be helpful in muddy conditions, especially during the rainy season. Be sure to pack regular hiking boots or shoes for the high elevation trails, but also pack your rubber boots for the wet season and for walking creeks.

Remember essential items like toiletries, sunscreen, mosquito repellent, and spare batteries. Sunscreen and insect repellent may be costly and hard to find, especially outside larger cities. Also, bring specialized items like camera batteries, memory cards, and accessories specific to your gear, as camera stores may not be readily available in remote areas.

Finally, flashlights are essential. In Panama’s tropical latitude, you’ll have roughly 12 hours of darkness each day, and primary forest canopies block most natural light, making visibility extremely limited without artificial light. I highly recommend carrying two flashlights: a headlamp for hands-free use and a handheld LED light, along with spare batteries and chargers. Having reliable lighting is vital; you won’t want to be without it in the rainforest.

Electrical Outlets in Panama

Travelers to Panama will be pleased to find that the country’s electrical system is compatible with that of the United States and Canada, making it relatively hassle-free for North American visitors. Panama uses Type A and Type B electrical outlets, the same two-pronged flat or three-pronged grounded plugs found in the U.S. and Canada. The standard voltage is 110–120 volts at 60 Hz, so most North American appliances, chargers, and electronics will work without the need for a voltage converter or plug adapter.

For travelers coming from Europe, Australia, the UK, or other regions that use 220–240V and different plug types, a plug adapter will be necessary, and in some cases, a voltage converter or transformer may also be required—particularly for devices that are not dual-voltage. Many modern electronics like laptops, phone chargers, and camera batteries are built for dual voltage (100–240V) and only require a plug adapter, but it's always best to check your device’s label before plugging in.

Power outages can occasionally occur, particularly during the rainy season or in remote areas, so travelers staying in jungles, off-grid ecolodges, or mountain towns should be prepared for temporary power interruptions. It's a good idea to carry a portable power bank for charging devices on the go, and if you're relying on camera gear or sensitive electronics, a surge protector or voltage-regulated power strip may provide additional peace of mind. Overall, travelers should have no difficulty charging or using their devices in Panama with minimal preparation.

As a wildlife photographer of nocturnal animals, I need to recharge many devices after every night, including rechargeable AAA bateries for my headlamp, a rechargeable Li ion led light, camera bateries, AA bateries for my flash, a cellphone (for the camera, downloaded maps, downloaded field guides, and compass/gps), etc. I find it usefull to bring a portable power bank that can be charging in the room while I'm in the field. When you only have one outlet in your room, charging from the power bank can be helpful to bring all your bateries up to charge before heading out into the field again. They're especially helpful when you need to charge from an outlet in a communal common area.

Packing Camera Equipment for Panama Wildlife Photography

In this section, I’ll provide a brief overview of the essential camera equipment to bring to Panama. For a more detailed discussion, please refer to the Camera Gear for Rainforest Wildlife Photography page. All photographers should bring several camera batteries and chargers, as well as multiple data storage cards. This isn’t just because you’ll be taking lots of photos, but also as a safeguard against theft, damage, or malfunctions. Spreading your photos across multiple cards ensures you don’t lose everything at once. Additionally, a flash is a must-have in the rainforest. Even during the day, overcast skies and dense canopies can significantly reduce ambient light, making a flash essential, especially for macro photography.

Pro tip: In the event of a confrontation with law enforcement, the officer may demand that you surrender your camera's sd card to him/her. Non photographers are often unaware that many cameras have two sd slots, and you might just want to keep one of those cards empty, in case you need to surrender one of them. Not only do you not want to lose your shots, if some of those shots have evidence of your innocence in the matter at hand, you'll probably want to keep those shots to yourself (This is advice I learned the hard way).

Herpetology Photography

If you’re focusing on reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates, you’ll want to bring a macro lens and/or a wide-angle lens for close-up shots, a flash, and a flash diffuser. Even if you prefer natural light photography, the low light levels in the forest often make flash photography necessary to capture clear, detailed images.

Birding Photography

Birding in Panama will require the same lenses and tripods you typically use for bird photography. However, the low light conditions you’ll likely encounter under the rainforest canopy and cloudy skies mean you may need faster lenses to capture as much light as possible. You might also consider adding a flash to your setup to improve your chances of getting the perfect shot.

General Wildlife Photography

For general wildlife photography, whether you’re looking to capture sloths, toucans, or reptiles and amphibians, a long lens is essential for birds and mammals, while a macro and/or wide-angle lens is ideal for closer subjects like reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and plants. A flash with a diffuser is usually necessary for macro photography in the rainforest, even during the day, and a flash without the diffuser can be used with the long lens. For a long lens, I recommend a 400mm or 500mm prime lens. The advantage of fixed focal length prime lenses, such as the Nikon 500mm PF lens (f/5.6), is that they are weather-sealed (perfect for the rainforest) and are lighter and more compact than their zoom lens counterparts.

Cell Phone Use in Panama

Staying connected while exploring Panama is relatively easy and affordable, with several options for both short-term visitors and long-term travelers. Whether you need mobile data for navigation and wildlife identification apps, or want to stay in touch with loved ones while off the grid, you’ll find Panama’s mobile infrastructure surprisingly well-developed—even in some rural areas.

Purchasing SIM Cards in Panama

For most travelers, buying a local SIM card is the most economical way to get connected. Major Panamanian telecom providers include +Movil, Claro, Digicel, and Tigo. These companies offer prepaid SIMs with affordable plans that include data, local calls, and sometimes international texting. You can purchase SIM cards at Tocumen International Airport upon arrival (look for kiosks or mobile carrier stores in the arrivals hall), or in shopping malls, electronics stores, and small kiosks in nearly every town and city across the country.

To activate a SIM card, you’ll need to present your passport, and your phone must be unlocked to accept a SIM from a foreign carrier. Most prepaid plans cost between $5 and $15 USD for a basic package with several gigabytes of data—plenty for Google Maps, WhatsApp, and casual internet browsing. If you're heading into more remote areas, such as the Darién or Caribbean islands, +Movil and Tigo are known for having the widest coverage, though Digicel and Claro offer competitive rates and coverage in many populated areas.

What is an unlocked phone? An unlocked cell phone can be used with multiple service providers, while a locked phone is tied to a specific carrier. Unlocked phones are more flexible and can be used with any compatible network, including international carriers. To find out if your phone is locked or unlocked, you can check your phone's settings. For example, on an iPhone, you can go to Settings, then Cellular, then Cellular Data. If you see "Cellular Data Network", your phone is probably unlocked. You can also consult your carrier's unlocking policy for more information.

Burner Phones in Panama

If you don’t want to use your primary phone abroad or your device is locked, you can buy a cheap prepaid burner phone—available at the same places that sell SIM cards. These basic phones typically cost $10 to $30 USD, come preloaded with credit for local calls and texts, and do not require contracts or long-term commitments. While they’re limited in functionality (usually without apps or mobile data), they’re a secure, low-stakes solution for travelers who just need a backup device for calling hotels, guides, or taxis.

Burner phones are also helpful for travelers venturing into remote rainforest areas or border regions, where reliable data coverage may be spotty but SMS or voice service might still work. Keep in mind, however, that these phones won’t support the apps or camera functionality of your smartphone.

International Phone Plans

Many travelers from the U.S. and Canada choose to use their existing carriers' international roaming plans for convenience. For example, AT&T’s International Day Pass allows you to use your domestic data, text, and call plan in Panama for $10/day, only on days you use it. Verizon’s TravelPass and T-Mobile’s international roaming plans offer similar functionality, with some including free texting and slow-speed data. These options are ideal if you want to keep your regular number, avoid the hassle of switching SIMs, and need reliable access during transfers between destinations or for emergencies.

That said, international plans are typically more expensive over time than buying a local SIM. A hybrid approach works well for many travelers: use your international plan only on travel days, and swap in a local SIM once you’ve settled into your destination. You can keep your original SIM card stored in a waterproof pouch alongside your passport, and continue using your phone on Wi-Fi or for photography without triggering international charges.

Transportation to and Within Panama

Overview: Panama offers multiple transportation options for getting to and around the country. This guide covers international flights into Panama, and the various ways to travel within Panama – focusing on key hubs like Panama City, David, Bocas del Toro, and popular eco-destinations (Boquete, Gamboa, El Valle de Antón). You’ll find practical details on airlines, buses, car rentals, private drivers, taxis, and domestic flights, complete with pros and cons, estimated prices (as of early 2025), and useful links for planning.

1. International Air Travel to Panama

Tocumen International Airport (PTY) in Panama City is the country’s primary gateway. It’s one of Latin America’s best-connected hubs, operating 24/7 with flights to over 80 cities (TOURISMPANAMA.COM).

Key Airports: Panama’s main international airport is Tocumen International Airport (PTY) in Panama City – recognized as the best airport in Central America & the Caribbean (2024) (TOURISMPANAMA.COM). It hosts numerous major airlines: Copa Airlines (Panama’s national carrier), plus United, American, Delta, Air France, KLM, Iberia, Turkish Airlines, and many others fly to PTY. Other international airports include Panama Pacifico (BLB) on the city’s west side (used by regional low-cost airlines), Enrique Malek International (DAV) in David (with some flights to Costa Rica), Scarlett Martínez (RIH) in Río Hato (serving beach resorts with seasonal charters), and Bocas del Toro “Isla Colón” (BOC) which has occasional international connections to Costa Rica.

Major Airlines & Routes: From North America, you can fly direct to Panama City on U.S. carriers (United, American, Delta), and from Europe on KLM, Air France, Iberia, and others. Copa Airlines uses Tocumen as its hub (“Hub of the Americas”), offering many flights across the Americas and some to Europe. For example, Copa and Delta have daily flights from cities like Los Angeles, New York, Miami, etc., and European airlines connect Panama with cities like Amsterdam, Paris, Madrid and Istanbul (some via stops).

Typical Airfare: Round-trip flights from the U.S. to Panama City average about $300–$500 per person (often on the lower end from Florida or Texas, higher from West Coast). From Europe, fares tend to range €600–€800 (~$650–$850) – for instance, a round-trip from Brussels via Madrid was about €720 including checked bag (kiladera.com). These prices fluctuate by season: expect higher fares in winter dry season (Dec–March) and around holidays. It’s best to book a couple of months in advance for good deals. As a reference, recent data shows an average flight price to Panama City around $417, with budget carriers offering occasional one-way deals under $100 from nearby hubs (restlesspursuits.com).

Best Practices: When flying into Panama, plan for a smooth arrival. Tocumen Airport is about 30 minutes east of downtown Panama City (longer in peak traffic). If you have a domestic connection (e.g. to Bocas del Toro or David), note that domestic flights leave from Albrook (Marcos A. Gelabert) Airport (PAC) across town. Allow at least 2.5–3 hours to clear immigration, collect bags, and transfer from PTY to PAC (a 30–60 minute taxi/Uber ride, costing ~$35 by taxi or less by ride-share). Panama does not require any separate tourist visa or tourist card for most nationalities (visa-exempt visitors get up to 90 days), and you can drive with your home country license for up to 90 days as a tourist. Departure taxes are generally included in your airfare. It’s wise to have a copy of your return ticket, as airlines or immigration may ask for proof of onward travel. Sources: solbungalowsbocas.com, expat-tations.com

2. Ground Transportation: Car Rentals vs. Buses

Traveling within Panama boils down to two main options for ground transport: rental cars or buses. Panama has an extensive and efficient bus network that reaches almost every city and town (panamarelocationtours.com), making it possible to get around independently for just a few dollars. At the same time, renting a car can offer flexibility to explore remote areas and move on your own schedule. Your choice will depend on your itinerary, comfort with driving, and budget. Here’s a quick comparison:

- Buses: Ubiquitous and ultra-affordable. Panama’s Gran Terminal Nacional de Transporte (Albrook Terminal) in Panama City is the hub where you can catch buses to anywhere in the country (panamarelocationtours.com, how to take the bus if you don't speak spanish). Long-distance coaches (to David, Bocas del Toro, etc.) are usually large, air-conditioned, and reasonably comfortable, though can be cold and take longer than driving. Local and regional buses (often colorful retired school buses nicknamed “Diablos Rojos” or mid-size vans) reach smaller towns. No need to book in advance – you typically buy tickets at the station and go. Cost is the biggest plus: fares are just a few dollars (see tables below). Downsides: you’re on fixed routes/timetables and may need to make connections for remote spots. Also, bus travel, especially overnight, can be very cold due to AC – bring a sweater for long rides! (panamarelocationtours.com)

- Car Rentals: Readily available in cities and airports, driving gives you freedom to set your own schedule and reach off-the-beaten-path locations that buses don’t go directly. For nature-focused travelers wanting to visit national parks, trailheads, or do a lot of stop-and-go exploring, a car can be ideal. Panama’s road network is generally good: the Pan-American Highway is paved across the country, and most tourist areas (e.g. Boquete, El Valle, Pacific beaches) are accessible by car. You can enjoy scenic detours and avoid the waiting or crowds of bus travel. However, be prepared for aggressive city traffic in Panama City (and minimal street signs), occasional potholes or unpaved roads in rural areas, and the extra costs of fuel, tolls, and insurance. Renting a car is much pricier than taking a bus – a typical economy rental runs about $30–$50 per day before insurance, and after mandatory insurance, expect to pay $70 USD per day (regardless of what the company advertises). Gasoline is about $1 USD per liter as of early 2025. Also note that some areas are not advisable or even possible to drive (more on that in the car section). Many visitors choose a mix: for example, take a comfortable express bus to David and then rent a car there to explore Chiriquí province.

The following sections dive deeper into each mode – with pros/cons, cost details, and tips to help you decide.

3. Pros and Cons of Bus Travel in Panama

Traveling by bus is the backbone of local transportation in Panama. It’s the preferred mode for most Panamanians and budget travelers. Below are the key advantages and disadvantages of bus travel, especially in the context of reaching eco-tourism destinations:

Pros of Bus Travel

- Budget-Friendly: Buses are extremely cheap. Even long cross-country trips cost under $30. For example, the 6-7 hour bus from Panama City to David is about $20 (nomadicmatt.com), and the 10-12 hour overnight bus to Bocas del Toro (Almirante) is around $25–$30 (kiladera.com). Shorter trips are just a few dollars (e.g. David to Boquete is $2 or less (panamarelocationtours.com), and local city bus fares in Panama City are $0.25–$1). This low cost makes buses the most economical way to see the country.

- Extensive Network & Accessibility: You can reach almost every town by bus. Major tourist spots have direct or frequent service – e.g. near-hourly buses link Panama City with David, and there are daily buses from Panama City to Almirante (for Bocas) and to other provinces. Even smaller eco-destinations are accessible: from David’s terminal you can catch regional buses to Boquete, Volcán, Cerro Punta, and beach towns. There are also local buses from Panama City to places like Gamboa (for Soberanía National Park) and El Valle de Antón. In short, Panama’s bus system is one of the most accessible and efficient in Latin America, which is a huge plus if you don’t want to drive. Additional resources: rome2rio.com, panamarelocationtours.com.

- No Hassle with Driving: By taking the bus, you avoid the stress of navigating unfamiliar roads or city traffic. You can relax, watch the scenery, or even nap on longer rides. This is especially nice for mountainous trips (where drivers can enjoy the view instead of focusing on hairpin turns). Bus travel also means not worrying about parking, fuel, or car security – just hop on/off and let the driver do the work.

- Cultural Experience: Riding Panama’s buses, especially the more local “chiva” buses or Diablos Rojos, can be a fun cultural experience. You’ll be riding with locals, maybe with some lively Latin music playing. It’s a great way to meet people or observe daily life. The main Albrook terminal in Panama City is a microcosm of Panama – bustling with food stalls and shops – giving you a taste of local travel routines. Additional reading: Riding Public Buses in Panama.

- Reasonably Safe: Despite some stereotypes, inter-city buses in Panama are generally safe. The coaches are in decent condition, and drivers are professionals. There is under-bus luggage storage for big bags (make sure your bag gets tagged and reclaim it with the stub). On the bus, keep your daypack or valuables with you. Petty theft is not common on upscale coaches, but as a precaution, stay aware of your belongings (especially in crowded city buses or terminals). Overall, travelers report that Panama’s buses feel safe – “cold, but safe” as one forum quip goes tripadvisor.ca.

Cons of Bus Travel:

- Longer Travel Times: Buses, especially non-express ones, can be slower than driving. For example, the Panama City–David bus takes ~6.5 hours with a couple of stops, whereas driving the same route might take about 5 hours in light traffic. Buses may detour to pick up passengers in towns along the way. Night buses allow you to “sleep” through the transi, with the slight upside of saving on lodging, but not everyone sleeps well on a bus. If you have a tight schedule, the time cost is a consideration.

- Fixed Schedules: While mainline routes are frequent, you’re still bound by bus schedules. Some destinations (e.g. a small mountain village or a trailhead) might have only a few departures per day. For instance, the bus from Almirante to Panama City leaves in the evening (and one in morning) – if you miss it, you wait many hours. Similarly, reaching El Valle requires catching a specific bus from the hub in San Carlos; missing the last one (late afternoon) means no way in that night. Planning ahead is needed to ensure connections (the table below provides some schedule hints). Also, buses can be full in peak periods, so arriving early to buy your ticket (or reserving the day before for popular routes) is wise– especially on holidays or Sundays when many locals travel. Sources: solbungalowsbocas.com, thelostandfoundhostel.com.

- Comfort Factors: Conditions vary. The express coach buses are modern with AC, reclining seats, and sometimes a bathroom onboard. However, that air-conditioning can be very strong – it’s not uncommon to see folks in sweaters or wrapped in towels on overnight rides because it feels freezing. Bring a jacket or travel blanket. Seating is first-come first-served (assigned seats only on a few premium services), so if you’re last on, you might get a less ideal seat. On older buses or local routes, expect less comfort: e.g. former school buses with tight seats and no AC, occasionally standing room only if it’s full. Roads in some areas can be winding (to Boquete or Santa Catalina), so motion sickness precautions might help if you’re sensitive. Despite these, most travelers find the comfort acceptable given the price – just don’t expect luxury. Source: panamarelocationtours.com